Down-to-earth wind power

The growing popularity of wind power to produce electricity with a low carbon footprint has led to the installation of wind turbines that are bigger and bigger. Now a small company in Switzerland is aiming at the other direction, producing wind power on a quieter, more down-to-earth scale.

Summary

WEPFER TECHNICS AG

Location: Andelfingen, near Zurich, Switzerland

Founded: Hans Wepfer started his own business in 1991 (Wepfer Technics since 2002)

Business fields: agricultural equipment sales, agricultural and industrial equipment development and manufacture, wind turbine manufacture

Employees: 11

Wind power is a most effective way of producing electricity with a very low carbon footprint, and the trend is towards ever-larger wind turbines. But Hans Wepfer, an inveterate inventor and tinkerer in Switzerland, has developed a small, efficient unit that fits neatly among the houses of a village or the buildings of an industrial estate.

Wepfer has built his company, Wepfer Technics of Andelfingen near Zurich, on his own inventiveness. He’s developed machinery for mowing grass, for picking sea buckthorn berries and for bevelling both the outside and inside of pipes in one procedure.

“Someone comes to us and says they need something that doesn’t exist,” he explains, “and we invent it.” He has several patents to his name, and some of his products are distributed worldwide.

The idea for the windmill came from his understanding of aeroplane propellers. Wepfer has a pilot’s licence, and if he makes use of something he needs to understand it. “I’m a completely mechanical man,” he jokes.

Given the need for energy sources that are low on carbon emissions, it seemed evident that he should use his understanding of propellers to de-velop a wind turbine. To do so, he had to develop the expertise to design the product, even making by himself the equipment needed to manufacture the parts.

But his research into those issues led him in the opposite direction from the present windmill industry. He explains, “You have to research whatever you do, and sometimes your research leads you from the known to the unknown.”

While the rest of the industry has been developing ever-larger units – nowadays, there are windmills with 60-metre-long blades and 140-metre-high masts, producing up to seven megawatts – his prototype turbine produces just 83 kilowatts, and its 7-metre blades are just 16 metres above the ground. A row of three turbines on one supporting structure, producing a total of 250 kilowatts, stands in an industrial estate in the nearby town of Schaffhausen and is operated by the local electricity company, EKS, which named it “Windmill3 Hans” in honour of its inventor.

The three turbines turn together over the buildings to face the wind, but they are so quiet that they don’t disturb the workers. Indeed, an earlier proto-type was standing just 30 metres from Wepfer’s own bedroom window. “At night,” he remembers, “I had to get up and look to check it was still working. I couldn’t hear it.”

His windmill is based around an innovative rotor design – its six blades are each much wider and flatter than those on a conventional three-blade unit. With six blades, the speed at the rotor tip is half that of a similarly sized three-blade rotor, and, according to Wepfer, that has several advantages, one of which is the absence of noise. At 45 decibels, the noise level is that of a quiet conversation.

Its quietness is one reason that Wepfer thinks it will be easy to get planning approval. He expects that his units will be put up in villages or on industrial estates because they won’t dwarf the surroundings. That enables decentralized electricity generation, which avoids transmission losses and takes some of the load off the network.

The big, flat rotor blades are harmless to birds and bats as well. According to Wepfer, they see the rotors as big discs, and they don’t come near. So far no animals have died in collisions with the prototype, but EKS is comparing the numbers of birds and bats before and after the installation. It could be that they simply avoid the area altogether now that these big “discs” are in the way.

But perhaps the main advantage is the efficiency of the new design. “We can start generating electricity when the wind is blowing at a speed of 1.5 metres per second, while conventional windmills need 3 to 3.5 metres per second,” Wepfer says. “In addition, we don’t need to turn the windmill off in a storm. We just adjust the pitch to maintain the planned generating level.”

The development of such an innovative design has not been without its problems. The main setback came when a rotor blade fell off the prototype and various aspects of the project had to be recalculated. In the latest version the problems have been solved, with carbon-fibre reinforced polymer blades to replace the original aluminium and steel construction, a larger main shaft and redesigned pitch control mechanisms.

Now Wepfer is getting ready for series production. The prototype was relatively expensive, with a lot of handicraft involved. The series will be more efficient in the production and more sparing in the use of materials. “We used 60 tonnes of steel in the prototype, and we’ll certainly get that down by quite a bit with a new design for the supporting structure,” Wepfer says. Some of the parts will have to be outsourced since Wepfer doesn’t have the capacity in his own workshops.

And there is plenty of interest: “We’ve had enquiries and visits from all over the world – even China and North Korea,” says Wepfer, “and we are planning to extend the range of products on offer.”

The turbines will be available as single units or as two, three or even four on a single construction. There will be smaller and larger versions, but Wepfer believes there’s a limit to the size before the design begins to lose its advantages.

“This is a milestone in my career as an inventor,” he says. “It’s quite a large project for us, and it’s quite different from anything that is currently on offer. I believe it is an important invention.”

As you might expect, Hans Wepfer won’t stop here. “This has led me to have other ideas for new products,” he says. “But I’m not telling you what they are.”

Central elements

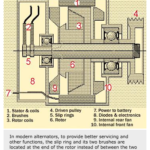

SKF supplies three central elements of Wepfer’s new windmill. The entire construction turns on an SKF slewing bearing fitted in a 2.5-metre toothed wheel. The propeller shafts are held at each end by an SKF spherical roller bearing and SKF housing, and the hydraulic pitch mechanism is supported by two angular contact ball bearings.