Cary Cooper

The workers’ champion

We know that overwork and stress in the workplace aren’t good for us or our families. But one British professor, Cary Cooper, has the facts and ures to back it up. And his aim is to get the word out – to help effect real change in workers’ lives.

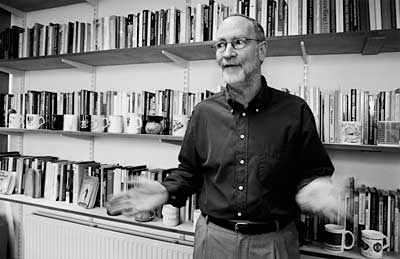

Cary Cooper sits in his new office at Lancaster University (in northern England) sipping tea from a mug emblazoned with the logo of his favourite football team, Manchester City. It’s an indication of how far Cooper, an American, has taken his adopted country to heart. Cooper took British citizenship 10 years ago, and Manchester City is one of his passions. So is improving the lot of British workers, along with that of their European neighbours.

Cooper is outspoken in his belief that the imbalance between work and home life causes a huge amount of misery to workers and their families. And this belief, backed by meticulous research, has earned him a high media profile and an international reputation as a “stress guru” in the field of occupational psychology and health.

Cooper has just left the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology where he was professor and head of occupational psychology and health to take up similar duties at Lancaster University, approximately 130 kilometres away. His office is already neatly organised. The walls are lined with books, many of them written by him. An old Edison gramophone sits on the floor, waiting for a home, and a row of mugs lines a shelf. One of them suggests coping with stress by strangling the boss.

If his name has a film-star ring about it, it’s because Cooper’s Romanian-born mother named him after her favourite film star of the 1940s, Cary Grant. The name “Cooper” has nothing to do with another Hollywood actor, Gary Cooper, but is, Cooper thinks, an anglicised version of his father’s Russian name. “My parents were both Jews who fled for their lives from Eastern Europe and settled in West Hollywood,” he says.

More compassionate

Cooper first came to Britain 30 years ago to continue his studies at Leeds University. He liked what he saw and stayed. “It seemed a more compassionate and civilised society, with its National Health Service and welfare support. I liked that, although a lot has changed, particularly since the ’80s,” he says, from behind his immaculate desk. Our conversation is overlooked by a teddy bear holding the message, “I’m stressed.”

Unlike many academics, he does not hide his light behind academic walls. His aim is for his research findings to be noted in high places and acted upon. “I focused on this work,” he says, “because I started to see what was happening in the workplace – the way employees were bullied and careers were blocked if you were a woman or an ethnic minority, the effect of increasingly long hours on health and family life.”

His research tends to be on the grand scale, with studies sometimes involving thousands of people. It was this kind of research in 1983 that led to him meeting Rachel Davies, a professor of design at Salford University. He employed her to help research the effects of stress on top interpreters, and they married shortly afterwards. He has four grown children aged between 18 and 30, including two from a previous marriage, and lives outside Manchester in Poynton, Cheshire.

Cooper’s list of commitments outside of work is literally breathtaking – the seminars he attends around the world, his research, the books he has written, not to mention the business psychology consultancy he co-founded in 1999. It’s hard to believe that he has any leisure time at all. But he learned to play the piano three years ago, swims at least three times a week, is an avid reader of Russian literature and actively supports his favourite football team. At 63, he has enough energy to do it all and still stay standing.

Create time

“I listen to what my research tells me, that overwork makes you ill and can lead to divorce,” he says. “The secret is to learn to say ‘no.’ You can’t do it all, and you have to create time for yourself. I like to come in to the office at 7:45 [in the morning] and finish at 4, so I can spend time with my wife and family. You won’t catch me working in the evening, unless it’s for an hour when my wife is out of the house.”

His efforts to bring humanity and compassion into the workplace are perhaps rooted in his student days in Los Angeles. While studying at the University of California, he worked as a social worker in one of the city’s most deprived areas. “I guess my desire to want to improve people’s lives came from those days,” Cooper says. “I’m a sort of an industrial social worker but with the science to validate my message. Or, perhaps seeing my parents’ insecurity because of their past made me want to make things better for them and for others.”

Cooper says the European workplace has changed considerably in the years that he’s been in England. “It has been Americanised, even in Scandinavia – especially Sweden, which has led the world in legislation and good employee-friendly practices,” he says. “In America, people are used to job insecurity, short holidays and being workaholics. Europeans are not used to that and had an infrastructure to protect them against it. They were used to working 9 to 5 and taking long lunches, often with their families. The dictates of globalisation have meant that to compete with America, Europe has had to do the same.”

The result is an insecure and stress-ridden work force, which in turn has resulted in an increase in divorce rates and work days lost through ill health. “Increasingly employers are not meeting their side of the contract, and workers are not being involved in the decision-making process,” Cooper says. “Employers keep people when they need them and dump them when they don’t. As a result, there is a huge increase in stress-related illnesses.”

Thank goodness, then, that Cooper is reminding us, both by personal example and through his research, that work does not have to be like that.