Shipbuilding to new heights

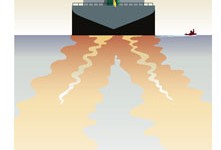

From sunset to sunrise in 20 years – it’s full speed ahead for the global shipbuilding industry as economies, especially in Asia, soar.

The global shipbuilding industryis in high gear. From South Korea, Japan and China – the three biggest shipbuilders in the world – to Romania, Brazil, Norway and France, shipbuilders are not only building more ships, but the ships are also getting bigger.

Shipbuilding has long had a reputation as a cyclical industry. Nevertheless, it is reaching new heights today as manufactured products increasingly pour out of booming economies such as China, Chile and Vietnam.

Increased trade quite simply translates into a need for more ships. And this activity rubs off on all related industries – ports, shipping suppliers, steel companies and so on. For example, the fleet of the world’s container ships expanded 9.8 percent in 2004 to a total of 3,362 ships. According to the leading shipping intelligence firm BRS-Alphaliner, the number of container ships is expected to grow at an annual rate of 14 percent until 2008.

“After the traumas of 2001, 2002 was a year of convalescence, and full health was restored in 2003,” writes BRS-Alphaliner in its 2004 annual report about the container ship market. “As for 2004, it was the year of superlatives. We have witnessed a shipping boom unseen since the early 1970s.” Unofficial shipbuilding data for 2005 point to a stellar year as well.

According to the same annual report, the number of container ships with a capacity of 7,500 TEUs or more (TEU stands for 20-foot equivalent, basically the size of a container) will grow by close to 50 percent a year, from 49 in early 2005 to 226 by 2009.

In January 2005, Hyundai Heavy Industries, HHI, the world’s largest shipbuilder, announced that it would build four of the world’s largest container ships at 10,000 TEUs each. The customer is China’s Cosco Asia, the lar-gest shipowner in China with a fleet of 600 ships.

These four leviathans will be 349 metres long, 45.6 metres wide and 27.2 metres high from hull to mast and will be too big for either the Suez or Panama Canal. These new super-sized ships will be able to

sail at a speed of 48 kilometres per hour.

This drive for bigger ships is based on the assumption that the shipping industry will continue to grow at a pace equivalent to the economic growth in China,

officially 9.4 percent (unofficially seen as much higher), especially on long-distance hauls linking Asia to Europe and North America.

The largest container ship to date, built by HHI for Germany’s Hapag Lloyd, can carry 8,200 containers, or TEUs. HHI has won orders for 35 ultra-sized container ships, controlling about 35 percent of this burgeoning market.

“There is a trend for global shipping firms to operate large-sized container ships to meet growing trade by ships,” says Hwang Moo-soo, an official at HHI’s shipbuilding business. “We are developing technologies to build even bigger ships, which can carry more than 12,000 TEUs of cargo.”

But super-sized ships also raise the question of

greater depth in ports. The port of Melbourne, the lar-gest container port in Australia, faced a channel depth

issue in 2002 in which some super-sized ships with a draft of 13 metres could not enter the approach channels that had depths of between 11 and 12 metres, depending on the tides. The channels had to be dredged to

accommodate the larger vessels.

Meanwhile, in December 2005, Shanghai, China, announced the building of the first phase of what could eventually become the world’s largest container port, a huge deep-water facility that will sit on an

island 32 kilometres out at sea.

The Yangshan deep-water port will accommodate super-sized tankers and could help Shanghai overtake Hong Kong and Singapore as the world’s biggest container port. Estimated volumes by 2020: 20 million TEUs (or 20 million containers), which represents a tripling of traffic through Shanghai.

But it is not only China’s portsthat are getting bigger. China’s shipbuilding industry surpassed Germany’s in 1995 and since has achieved an annual sustained growth over the past few years of around 17 percent. In July 2005, China announced that it would build the world’s largest shipyard on Shanghai’s Changxing Island, a major step forward in China’s stated ambition to become the world’s leading shipbuilder. China currently builds about 15 percent of the world’s total tonnage of ships and is ranked No. 3 in the world after South Korea and Japan.

Just about every type of ship imaginable – except for cruise ships, which are primarily built in Europe – is coming out of dry docks on China’s eastern coast. The ships include bulk carriers to haul raw materials, container ships and liquid natural gas carriers. Most Chinese shipyards have order books that are filled for the next four years.

But China is not the only place where shipbuilding capacity is growing. In Brazil, the state-owned oil company Petrobras is engaged in a 42-tanker deal with local shipyards. Keeping the jobs in Brazil (“build Brazilian”) was the wish of Brazilian President Luiz da Silva, and it will help reinvigorate an industry that in the late 1990s was virtually dead.

On the European front, it was announced in early 2006 that French engineering conglomerate Alstom would join forces with Norway’s Aker Yards to create a shipbuilding giant. Alstom owns the famed Chantiers de l’Atlantique shipyard in St Nazaire, France.

Another place where shipbuilding is surging is in Eastern Europe. In April 2005, the Daewoo Mangalia Heavy Industries shipyard in Mangalia, Romania, on the Black Sea, booked orders worth 850 million US dollars from Germany for 10 container ships. In press reports, Daewoo Mangalia president MK Lim has said the yard would have revenues of USD 1 billion by 2015 and would become Europe’s leading shipyard by then.

According toMartin Stopford, from the Erasmus Centre for Maritime Economics and Logistics at the Erasmus University School of Economics in Rotterdam, Holland, the transformation of the shipbuilding industry in the past 20 years has been nothing short of extraordinary.

“Back in 1988, production slumped to 15.2 million deadweight tonnes, earning the shipbuilding industry the tag ‘sunset industry,’” says Stopford. “Since then, shipbuilding has grown at 10 percent per year or more, making it one of the world’s growth industries. The sun is certainly shining on the shipyards today. Ship-building has become a sunrise industry.”