At a crossroads of cultureIn September 1993, Sweden’s Volvo and France’s Renault announced plans to merge. The union was hailed with cheers by auto industry analysts who saw it as a marriage made in heaven. Combined the two automakers would create one of the largest car-and-truck manufacturers in the world and achieve drastic reductions in costs.

Yet despite all this, the merger attempt failed. Opposition from Volvo shareholders dogged it on one side; French trade unions spurned it on the other.

In fact, as Terry Garrison points out in his book International Business Culture, (Elm Publications, Cambridge, second edition 1998), cultural factors were really what threatened the merger. “Sweden’s Volvo shareholders saw the merger as the imposition of foreign control,” Garrison says, “while Renault’s workers, the French government and many shareholders in France believed that the company was special, a state-owned model of integration between workers and management that they wished to see preserved. These cultural values won out over the economic questions involved.”

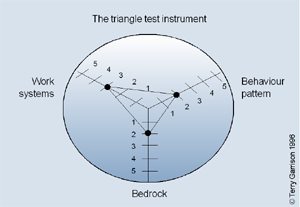

For Garrison, the failure of the Renault-Volvo merger is typical of the way businesses contemplating cross-border link-ups ignore cultural factors – at their peril. “It is essential to understand what I call the cultural ‘bedrock’ of your international partners, to explain where these people are coming from,” Garrison says. “When you understand that, you can make intelligent decisions about how to manage the relationship.” To grasp them, Garrison created something called the “Triangle Test,” which today is one of the most widely accepted practical methods that businesses can use to handle cross-cultural gaps. “The Triangle Test provides a straightforward, clearly defined way to analyse these questions,” Garrison says.

Culture is Terry Garrison’s business. Or, to be more accurate, Garrison has spent much of his career studying the ways in which cultural factors affect international business.

However, Garrison himself seems an unlikely protagonist for multicultural issues. Wearing a classic English suit, he looks the very model of an Oxford don, and his speech bears the refined nuances typical of the academics of that ancient institute of learning.

Yet Garrison has little in common with such a stereotype. After graduating from Oxford with a master’s degree in Russian and German, he studied public administration at Brunel University in the U.K. and international marketing at Cambridge. As export manager, he travelled throughout the world for Glaxo Laboratories and the International Publishing Corp, doing business with other cultures.

Garrison began teaching management in 1970 at Slough College of Higher Education, then joined Henley Management College in 1990, where he now runs the International Management faculty. His work involves studying the problems of cross-cultural business in the strategic context. He teaches worldwide in Henley’s Distance Learning MBA programme.

Garrison’s approach is interdisciplinary. “The areas I deal with involve anthropology, sociology, psychology, economics and politics,” he says. “But a strictly academic approach would be too confining. I work at applied solutions, not just research.”

The first solution that Garrison describes in his book is the “iceberg” model. At the tip of the iceberg are the more superficial manifestations of culture – how people talk to each other, what languages they speak, how the society functions – Do trains run on time? How are workers hired and fired? These issues, he says, answer the question, “How are things done around here?”

But below the surface lies the bedrock – the historical, societal and religious factors that really govern what we see on the surface. These include the pattern of ownership of a nation’s businesses, and its religious, political and economic systems, the resource profile of the country and the key features of its history.

“The result enables one to take a global view of a different culture,” Garrison points out. “Are your foreign colleagues self-confident or ambivalent? noisy or reticent? proud or humble? active or passive? aggressive or defensive? persuadable or hard-line? Much will depend on individual psychologies and the specific culture of the company for which they work. But it will also be affected by all the bedrock factors.” Understanding both will enable you to work with them better, he says.

To obtain this understanding, Garrison invented the Triangle Test. It is used in situations that need to be dealt with by a cross-cultural team. In an international merger or takeover situation, for example, the people dealing with it come from different nationalities and must learn to collaborate.

Garrison provides team members with three series of statements, which evoke attitudinal differences. Respondents score each statement on a scale of one to five – “I agree entirely” to “I disagree entirely.” Scores on the questions indicate which of these will figure significantly in the situation at hand. The scores are projected onto a triangle (see illustration).

When the scores are linked and projected on the triangle, each national firm in the partnership will have a different shape. The comparison allows Garrison to tell where the points of agreement, and more important, where the points of potential conflict are most likely to arise. It is a highly practical, empirical way of handling management problems.

It is also a way to test reaction to change. “Had Volvo used the Triangle Test on workers at Renault before announcing the merger, they would have perceived that a severe reaction to its plans was inevitable,” says Garrison.

The great advantage of the Triangle Test is that it provides a practical and straightforward method of handling cultural differences. “It places the problem in a format where it is easy to grasp,” Garrison explains. “It is not rigorous social science, but it works.” Garrison gives the example of a Miami-based American bank that acquired a group in Bolivia. “When the researcher gave the Triangle Test to workers at the South American bank, they found the statements very disturbing, reacting almost invariably with a high level of disagreement. This showed the American bank just how different the Bolivian one was, and how much work would be required to convert it to the American model.” The American bank slowed down plans to restructure the facility as a result. What’s next for Garrison? He has already worked as a consultant for Motorola, Sony, BASF, the Bank of New York, British Gas and many other companies. “As globalisation continues, I expect I will do much more,” he says. As visiting professor at Turin Business School and the Centre de Recherches des Cadres in Paris, he has opportunities to do so.

“There are a lot of bedrock cultural differences in the world that still need explaining to more and more concerned executives,” he says, laughing. “They have no choice but to understand more of the Global Village we all live in.”

Andrew Rosenbaum

a business journalist based in London

photos John Cole