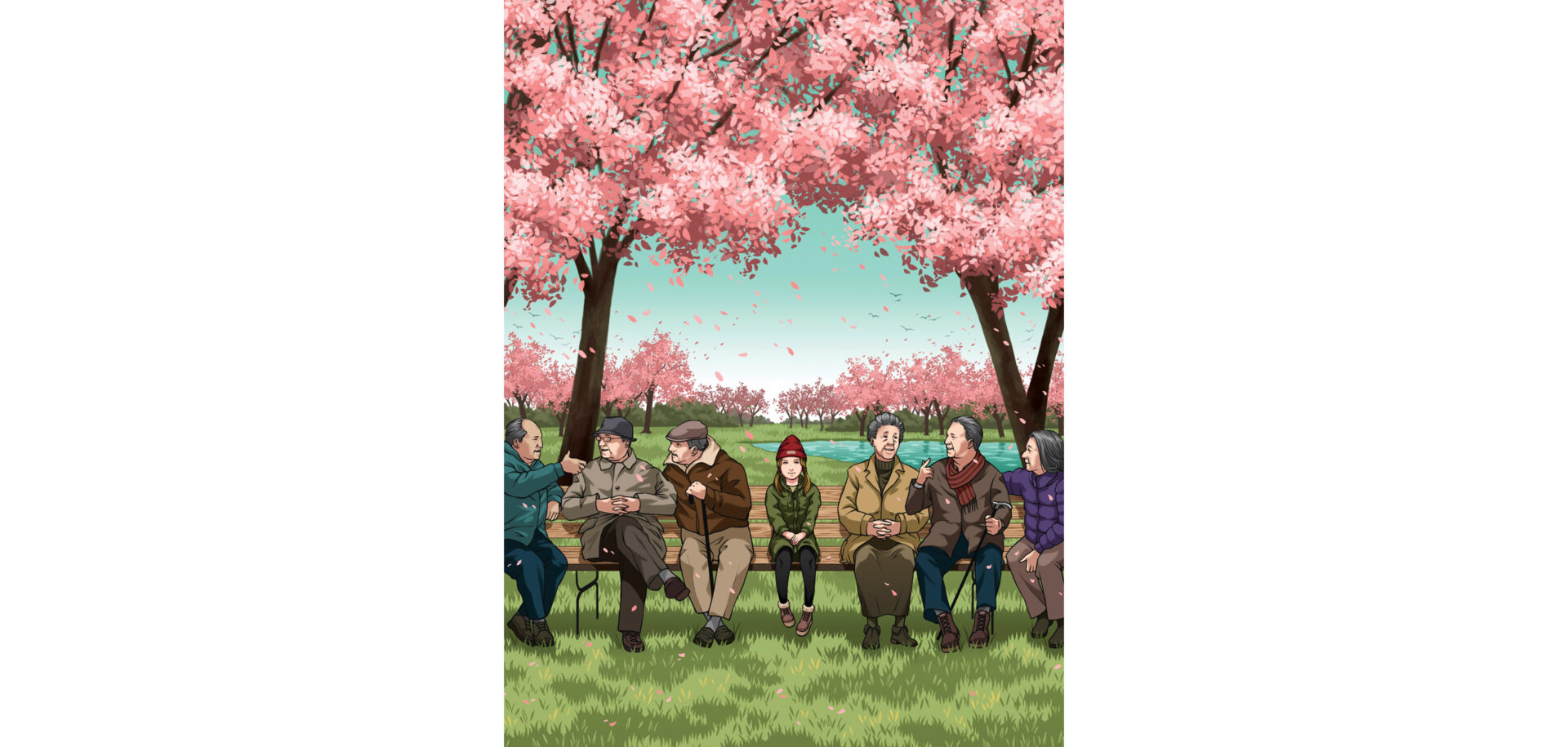

Grey goes global

As older people start to outnumber children in many countries in the world, governments and businesses are facing the realities of the new ageing population and the implications for public policy and economic growth.

Falling birth rates and longer life expectancies have created a global phenomenon: population ageing. Over the next four decades the number of people over the age of 60 is expected to more than double to more than 2 billion people, according to the United Nations. By 2050, for the first time, older people will outnumber children – something that has already happened in long-time developed countries. This unprecedented demographic change poses a huge challenge to policymakers. How will they fund pension and health-care systems, which typically account for 40 percent of government spending, and maintain a healthy level of economic growth if there are fewer workers supporting a burgeoning older population? Michael Hodin, executive director of the Global Coalition on Aging, says governments need to start by changing their thinking about ageing in a “profound and fundamental” way. One way to align the economic models to the 21st century demographic reality is to scrap the retirement age. “The age 65 is an artifact – it was a year picked by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s and later reaffirmed by US President Franklin D Roosevelt in the 1930s,” Hodin says. “It might have been applicable when we died a few years after 65, but we are now living longer, and economically it makes no sense to have that as a fixed date.” In fact, many older people, if given the choice, would rather stay in their jobs than be put out to pasture, partly because they don’t have enough money to fund their retirement, but also because they are healthy and feel they still have something to offer. A 2014 survey of baby boomer workers, conducted by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, found that 65 percent of the respondents planned to work past the age of 65 or had no plans to retire. More and more companies are starting to realize that older employees can be an asset and are making it possible for them to keep working by offering more flexible hours and conditions. But the older population isn’t just a source of workers for companies; it’s also a significant money-making opportunity. Unburdened by the need to support young families and armed with significant savings, this older global cohort is projected to spend USD 15 trillion a year by the end of this decade. Companies such as Nestlé are starting to catch on. The Swiss food giant has changed the packaging of some products to make them easier for older people to use. Sarah Harper, director of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing at the University of Oxford, says the ideas around the traditional chronology of people’s lives have to change, and part of that means pushing back the retirement age. But she warns that a one-size-fits-all approach risks “leaving people behind”. “One of the problems is there are huge differentials between the ability of people as they age,” Harper says. “Those with less education and who have maybe had unhealthy lifestyles may not be able to continue in the labour market in their 60s and early 70s, whereas more highly educated people, professionals who may have had a healthier lifestyle, have a far greater healthy life expectancy. That means they may be very capable of working into their 70s,” she says. Policymakers have strong economic reasons to act. Apart from reducing pressure on already strained pension and health-care systems, increasing the participation rate amongst older workers could boost economic growth. In the eurozone, for example, the average GDP growth rate per capita is estimated to reach 1.3 percent a year up to 2050 if more people over the age of 50 keep working, according to a study published by the International Longevity Centre in the UK. That’s compared with 1 percent growth if they don’t. Failure to do something could lead to “increasingly unsustainable” fiscal pressures, according to Standard & Poor’s Ratings Service. It estimates that increased age-related spending could lead to government debt-to-GDP ratios rising by an average of more than threefold in developed countries and about fivefold in emerging markets by 2050 if policies don’t change. Many countries have read the writing on the wall. Australia, for example, has increased the retirement age to 70 for people born after 1965 and introduced tax breaks to encourage older workers to stay in their jobs. Singapore has rolled out training programmes for older people, while France has raised the level and duration of pension contributions. “Give me an additional 5, 10, 15 or 20 percent of those who are retired and keep them working and active, and that will lead to economic growth that will be enormous,” says Hodin.

“If you maintain 20th century approaches on tax policy, on pension policy, on labour policy and on when to retire, you should be worried because it will wind up being a disaster – there’s no question about it,” Hodin says.