Heavy lifting

At SSAB’s sheet steel mill in Luleå, Sweden, great care is given to the 15 overhead process cranes that transport and tip 100-tonne ladles of molten steel from one stage of steelmaking to another. Without the cranes, production would stop.

At SSAB’s sheet steel mill in Luleå, Sweden, great care is given to the 15 overhead process cranes that transport and tip 100-tonne ladles of molten steel from one stage of steelmaking to another. Without the cranes, production would stop.

Business

There is more to steelmaking than all the metallurgical and alloying processes in a steel mill. Keeping the equipment such as the massive process cranes up and running is critical.

“Maintenance is cheap; downtime is expensive,” says Jan-Ola Wanhainen, the SSAB person responsible for the cranes at the Luleå steel mill. His vision is to have 100 percent uptime with his cranes.

These are no ordinary cranes. Instead, like a blast furnace or a continuous casting machine, these huge wall-mounted and ambulatory overhead cranes are part of the infrastructure for the proper functioning of the Luleå steel mill.

“In a steel mill every piece of equipment is important,” says Wanhainen. “We are only as strong as our weakest link.”

At SSAB Tunnplåt (sheet steel) in Luleå, the steel making process starts with cooking imported coal to make coke in the coking plant. This process produces a lot of gas, which is then recycled to heat the steel mill and half the town of Luleå, with its population of 45,000 people.

Over in the blast furnace, the coke is used as a fuel together with oxygen to melt the iron ore pellets that come to Luleå daily by rail from LKAB in Malmberget, situated some 200 kilometres from Luleå.

The molten metal is then transferred to the steel mill in 300-tonne increments and transported a short distance by rail in a cigar-shaped railcar known as a torpedo.

Transferred to a furnace the size of a house, the molten metal is injected with carbide or magnesium oxide to remove the sulphur content.

In another furnace, high-pressure oxygen is added to blow out the carbon in the molten iron. The iron is converted into steel when the carbon content is below 2 percent.

Fine adjustments are then made to the temperature and composition of the steel before it gets carried over to a continuous casting machine where the molten metal solidifies into 25-tonne, 11-metre-long slabs of steel. Three hundred of these are produced everyday at Luleå, equivalent to an annual production of 2.7 million tonnes.

The slabs are transported by rail to SSAB’s rolling mill in Borlänge where they are rolled into different thicknesses and can be quenched, hardened, tempered and after-treated, depending on customer preferences.

The sprawling hangar-sized halls with their gigantic furnaces, massive cranes and ladles of molten metal give the Luleå steel mill the atmosphere of a science-fiction film.

But appearances are deceiving. Behind the grit, the noise and the smoke is a very high-tech computer infrastructure that monitors all the parameters of the steel production.

For example, overhead crane operator Stefan Näslund handles the 100-tonne ladle of molten steel remotely from computer screens in a control room, taking his cues from 300 manoeuvrable video cameras strategically deployed throughout the steel mill to give him the best view possible of what’s happening on the floor.

“It wasn’t that long ago [December 2008] that I would sit in the crane up by the ceiling and steer the ladles via a walkie-talkie with someone on the ground,” he says.

Some of the overhead cranes in the SSAB facility in Luleå can also be steered by remote controls, not unlike the kinds used by model airplane enthusiasts.

Even the locomotive that steers the torpedo railcars from the blast furnace to the steel mill is remotecontrolled.

As of late 2009, SSAB Tunnplåt in Luleå became the first steel mill in the world to install SKF online condition monitoring equipment on its newest crane motors and transmissions (see sidebar).

Wanhainen likes to show visitors a crane from the 1940s that is still at the mill, standing idle in a recess. To operate the crane two men had to manually pull on chains via a pulley system, and the quantities the crane could lift were but a fraction of the volumes of steel in suspension today.

“We’ve come pretty far,” says Wanhainen.

First crane application

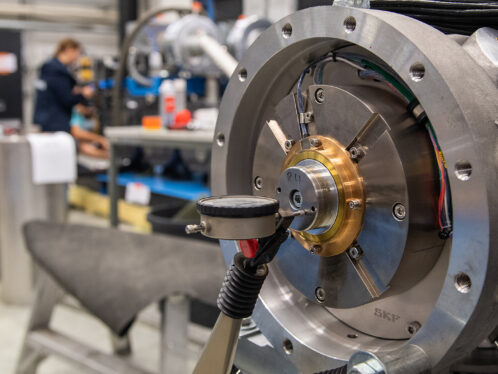

SSAB Tunnplåt in Luleå, Sweden, is one of the first big industrial groups in the world to install SKF online conditioning monitoring systems on the motors and transmissions on five of the company’s newest overhead process cranes.

SSAB uses the SKF Multilog On-line System IMx-S to get real-time information about the condition of the bearings in the motors and transmissions via sensors in order to continuously monitor machine reliability when the cranes are in operation. The data is monitored by SKF.

“An unplanned stop in a steel mill is catastrophic, given the volumes under production,” says Jan-Ola Wanhainen, responsible for all the cranes at the Luleå steel mill. “So we need as much information as possible before we go out to a crane for a planned maintenance stop, and this online condition monitoring really shows when and where things go wrong.”