Made in Africa

With labour costs rising in Asia, manufacturers are turning their attention to Africa. Will the continent become the next centre of global manufacturing?

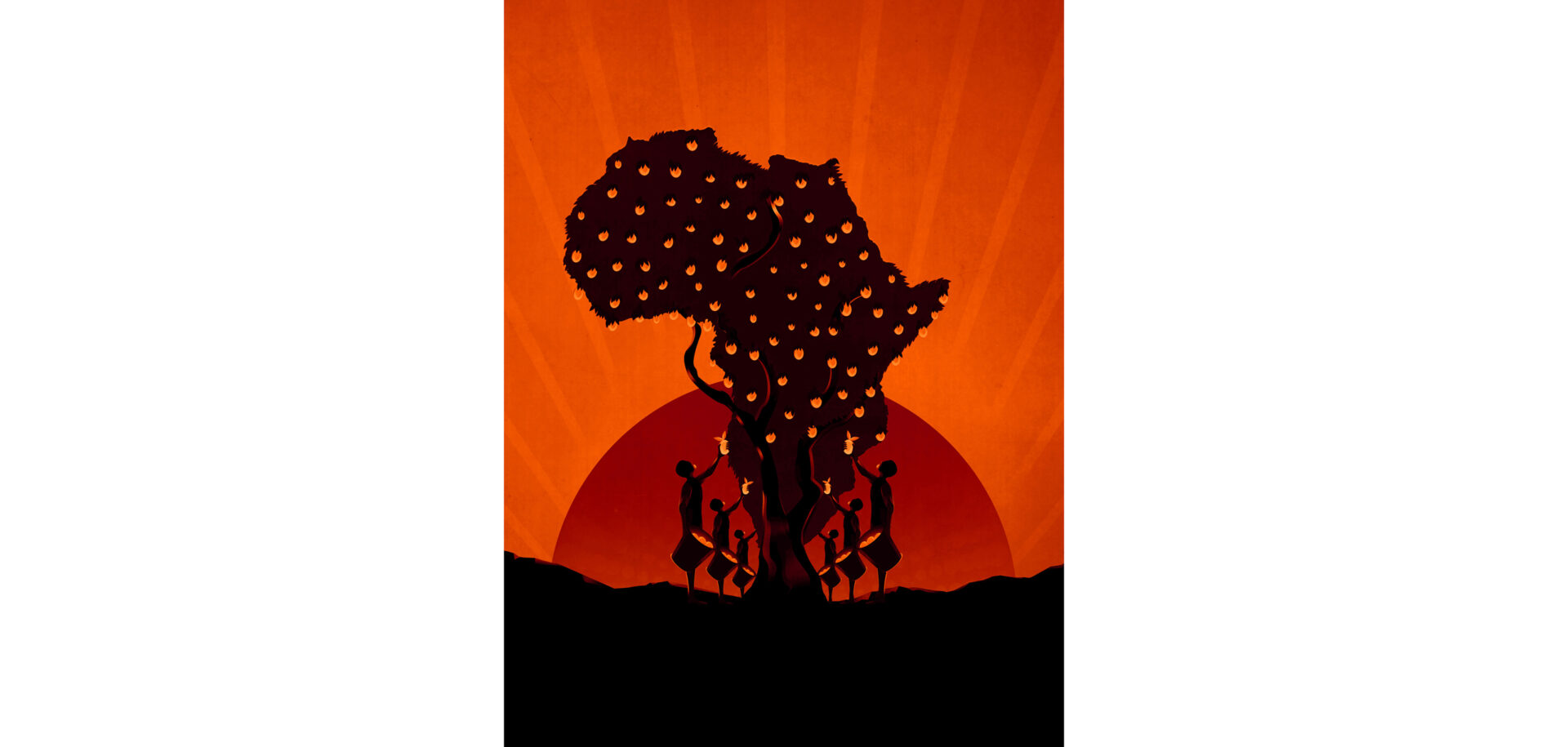

For many countries around the world, manufacturing represents a path to sustainable growth and development. “No country can industrialize without going through the phase of manufacturing,” says Hinh T Dinh, a lead economist at the World Bank and lead author of Light Manufacturing in Africa: Targeted Policies to Enhance Private Investment and Create Jobs. “Most countries reach a manufacturing ratio of 20 to 35 percent of the economy before the percentage starts dropping with the growth of services and other sectors.” In Africa, however, Dinh says, manufacturing’s share of the economy has declined for the past three decades – today it is only 9 percent – and unemployment remains high. He explains, “In Africa, there are more than 50 countries, so it’s very difficult to generalize, but by and large manufacturing has not been taking the road it should have been taking. In the 1960s and ’70s, the continent followed the economic development strategy that prevailed at the time: heavy state investment in sectors that led to state-owned enterprises. Then it swung to the other extreme, which basically meant that everything was left to market forces. Everyone now recognizes that leaving it to market forces is not the answer.” Many African countries are stuck in “low equilibrium”, Dinh says, and explains: “The countries are too poor to invest in the infrastructure, human resources and financial resources that are needed, and there is a vicious circle of low industrialization and pervasive poverty.” On the other hand, Africa is seeing relatively substantial growth of 4 to 5 percent in GDP. “This is due to a price rise in the international market for commodities, mostly mineral resources,” he says. “But this type of GDP growth does nothing for unemployment and is unlikely to be sustainable.” Nevertheless, Dinh and other economists see a number of factors coming together, raising hopes for Africa’s economic future. “Over the past decade, when you look at China, costs have been rising along the coastal areas, and now even in the interior provinces,” he says. “It is becoming no longer profitable for Chinese companies to manufacture low-end consumer goods, so there is an opportunity for African countries.” Adam Elhiraika, director of the Macroeconomic Policy Division of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, lists several of Africa’s advantages: “Human capital in Africa is improving through education, as primary school enrolment is more than 90 percent in most countries, and the higher education system is expanding and developing. It’s easier now than ever before to find workers who are tenable. Domestic demand is becoming more important, and inter-African trade is growing, and this is increasing the size of the market.” Dinh points out that many markets set favourable pricing for African imports. But another important factor is the considerable natural resources that many African countries have – oil, minerals and agricultural resources. Elhiraika believes that with government support, commodity-based industrialization is possible. “Not all African countries have commodities, but those that do should have policies in place to produce goods for domestic and external markets,” Elhiraika says. “For example, in Botswana, the government introduced policies to cut and polish diamonds locally, and this has built up an entire industry.” Dinh agrees that government intervention is needed, despite the experience of the 1960s and ’70s. “There are lots of government interventions that don’t require financial resources, and there are lots of policies that can be put in place to promote manufacturing,” he says. He would like to see governments identify the specific binding constraints for various promising sectors and address them promptly. In Africa, the six major constraints to manufacturing tend to be the availability and quality of raw materials, difficult logistics, access to land, access to finance and the skill levels of workers and managers. He cites Ethiopian leather as an example. “In Ethiopia, for most of the cattle that are slaughtered, the skins aren’t used,” he says. “There are several reasons for this, but the most important is an ectoparasite that leaves a blemish on the skins, making them unusable for leather. The treatment is simple, a vaccination two times a year, at a national cost of less than 7 million euros. This is where government is needed; the producer of the shoes can’t fix the ectoparasite problem, it needs the involvement of the agricultural sector. We’ve been advocating for these kinds of selective, targeted policy interventions.” Elhiraika says, “We have seen periods of growth before, not just in commodities. But there are other factors now that lead me to be optimistic about Africa’s future: the expanding domestic consumer market, improving government management of the economy and diversification of economic relations globally. And while manufacturing has stagnated or declined relative to the economy, in absolute terms it has increased.” About 15 years ago, entrepreneur Ryaz Shamji started up Golden Rose AgroFarms Ltd, the first highland rose export company in Ethiopia. Shamji saw that Ethiopia offered favourable growing conditions as well as closer proximity to market – Europe and the Middle East – than Kenya, where his closest competitors were located. Today, the Ethiopian floriculture export industry has grown to become the fourth largest in the world, employing more than 50,000 workers and generating 145 million euros a year. “All this growth has helped villages to become towns and for families to afford to send kids to school,” Shamji says, “thereby creating the opportunity to break out of the downward spiral that comes from subsistence farming.” As a businessman, Shamji believes in Africa’s potential. “I cannot begin to express the scale and scope of opportunity for manufacturing across the continent – in all sectors. The advantages can be first-mover advantage, lack of competition, land availability and access to natural resources. There is huge opportunity for export and import substitution.”Opportunity blooms in Ethiopia