Mining the extreme north

At 78 degrees latitude, Svea is the world’s northernmost underground coalmine and the only one in the Nordic region.

At 78 degrees latitude, Svea is the world’s northernmost underground coalmine and the only one in the Nordic region.

Located 1,000 kilometres from the North Pole, on Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, Svea has battled impossible conditions and setbacks in its 92-year history, but it is now one of the world’s most modern underground coalmines.

Norway’s state-owned Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, or SNSK, is the operator.

SNSK’s logo, emblazoned on its fleet of four-wheel-drive Toyota pickups that drive in the mines, shows a polar bear family with two cubs – an impossible image. Polar bears don’t come in families, and males tend to

eat their young.

The association with impossibility is fitting for Svea.

“Many have tried and failed to mine coal profitably on Svalbard,” says Gunnar Andreas Aarvold, Svea’s maintenance manager. “We have proven that the impossible is possible, which is why our logo is an inspiration.”

Svalbard is an arcticwilderness of the grandest proportions. But it is pockmarked with many abandoned or destitute mining settlements, such as the Russian mining settlement of Barentsburg, which had to flood its mine in 2008 because of fire.

Svea, however, is thriving, despite the disastrous fire it suffered in 2005. The fire caused a year’s production loss and generated one of the biggest insurance claims in Norwegian history.

The Svea mine is located 60 kilometres southeast of Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s capital, but due to the geology and adverse climate there are no roads connecting the two places.

Svea is reachable by air (it has its own airstrip), by snowmobile (watch out for polar bears, reindeer and arctic fox) or by ship. But the Van Mijenfjord is only navigable and ice-free between July and December, so Svea has to stockpile its coal for half the year.

Thus the Svea mine’s location poses unique logistical problems in terms of supplying the mine with parts, machinery, food, diesel and personnel.

The huge Caterpillar bulldozers that are used to push coal around at Svea’s port for loading onto ships during the summer and autumn are often used during the winter to pull 40-tonne containers full of supplies on special sleds across the mountains from Longyear-byen – a 24-hour journey roundtrip.

But supplying the mine and the settlement, often in temperatures of –30 degrees Celsius, is a piece of cake compared with the actual work of extracting coal from depths of six kilometres inside a mountain.

“The problem every mine in the world faces is to synchronize the development work on a new seam – roads, access tunnels, ventilation, electricity, water, air, conveyors – while excavating an existing seam, to ensure continuous production,” Aarvold explains.

At Svea, it takesbetween eight months and a year to excavate a seam of coal, which typically is four metres high, 250 metres wide and three kilometres long. It takes about the same amount of time for the development work on an adjacent seam.

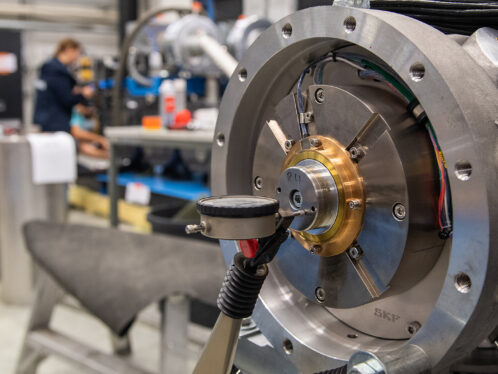

The heart of the operation is a JOY longwall machine, which has powerful cylindrical shearers that rip through 80 centimetres of coal at a time. The machine works its way back and forth along the long wall.

Depending on the consistency of the rock, the machine can advance 10 to 20 metres a day.

“With all the appending equipment that has to follow – transformers, generators, hydraulics and so on – it is like moving an SKF factory every day,” observes Aarvold.

The operators stand underneath a hydraulically secured roof, which miraculously advances as well, and operate the machine remotely. It is dirty, dusty and demanding work, but the miners are handsomely paid.

After the coal has been ripped from the walls of the mine, a robust conveyor system channels the coal through a separate 13-kilometre-long tunnel to the Svea settlement.

There, sounding much like a waterfall, the coal spills out into the open air to form a pyramid, from which a bulldozer shovels load upon load into heavy Volvo trucks for further transport to the port, 12 kilometres away.

Between July and December every year, about 70 ships, some of Panamax size (with displacements of more than 70,000 tonnes), sail up to Svalbard to load up on high-quality Norwegian coal.

“When I arrive on Monday, I need to see and hear this waterfall of coal; otherwise I know it is going to be a hellish week,” says Aarvold. Aarvold lives with his family in Longyearbyen but commutes by snowmobile to Svea during the winter.

A long history

Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani was founded in 1916 when it took over coalmining operations on Spitsbergen from the American Arctic Coal Company, which was led by John Munro Longyear, who lent his name to the island’s capital, Longyearbyen.

In 2007, SNSK had a turnover of 2.2 billion Norwegian kronor (256 million euros), 400 employees and produced 4.1 million tonnes of coal. The Svea field was acquired from Sweden in 1934 – hence its name – but it didn’t start produ-cing fully until 2001.

The Svea Nord field has commercially viable reserves of about 17 million tonnes, enough for eight more years of operation. Another find, in Lunckefjell, is being considered and could be viable by 2014, with reserves up to 2019.

A majority of the coal is shipped to clients in Germany, England and France; 54 percent is used in power plants, 28 percent in the steel industry and 18 percent in the cement industry.

SNSK has historically played an important role in developing and maintaining the community in Longyearbyen, although the management of social services such as schools and hospitals was taken over by the Norwegian government in 1989.