The benefits of remanufacturing rolling bearings

Remanufacturing bearings can help companies reduce downtime, save costs, reduce scrap and support sustainability.

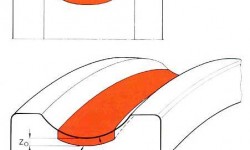

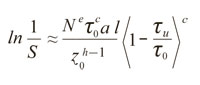

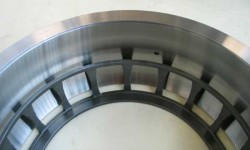

For decades it has been a practice in commercial/industrial and aircraft applications that rolling bearings removed at maintenance and overhaul are reworked and returned to service. The effect of rework of components and elements can be evaluated. Bearing rework gives many cost benefits. Savings can be 50 to 80 % depending on bearing condition, size, etc. Furthermore, reworking has a strong sustainability impact: 100 kg of reworked bearings will save approximately 350 kg of CO2 emission. Algebraic relationship can be established to determine the L10 life of bearing raceways subject to partial removal of stressed volume as a function of the depth z at refurbishment and restoration. Depending on the extent of rework, the life factor LF for a reworked bearing may range from 0.87 to 0.99 of the life of a new bearing. Bearings are core components of plant assets, and they take a lot of punishment. Usually, bearings are either replaced during planned maintenance when nearing the end of their operational life or after unplanned breakdowns. Depending on the bearing type, replacement can be expensive and may involve long lead times. In addition, scrapping of “end of life” bearings may have a negative impact on a company’s sustainability profile – an aspect that is becoming increasingly important to investors and customers. How can one increase the service life of bearings in order to decrease downtime, reduce costs and reduce scrap? Remanufacturing is the key (figs. 1 and 2). Cost-benefit analysis shows that potential cost savings of between 50 to 80 % of the cost of a new bearing can be achieved by remanufacturing bearings – depending on bearing size, complexity, bearing condition, price, etc. Furthermore, remanufacturing of used bearings can reduce CO2 emissions. Remanufacturing 100 kg of used bearings leads to a reduction of about 350 kg of CO2 emissions. In the aircraft industry, amongst others, it is common practice to remove rolling bearings at maintenance or overhaul for reworking. The bearings are subsequently returned to service [1 to 3]. A need for an international standard (ISO) is seen to ensure that there are defined procedures and terms of reference. Currently, only a national Austrian standard [4] has been agreed; this was published in 2011. For remanufacturing of used rolling bearings, five classes have been established. It is possible to describe the bearing life for remanufactured bearings considering changed geometry and shear stress τ (τ0, τu) due to stressed volume removal and to the effect of replacing the rolling elements with a new set. Generally, a rolling bearing cannot be used and rotate forever, unless operating conditions are ideal and the fatigue load limit is not reached; sooner or later material fatigue does occur [5]. Bearing life is considered as the period until the first sign of fatigue appears. The bearing life is a function of the number of revolutions performed by the bearing and the magnitude of load [6 to 9]. Fatigue is the result of shear stress cyclically appearing immediately below the load carrying surface of the ring(s) and rolling elements (fig. 3 and equation 1). S survival probability [%] N number of load cycles τ0 maximum orthogonal shear stress [Pa] τᵤ fatigue limit shear stress [Pa] z0 depth of maximum orthogonal shear stress [m] a contact semi-axis in transverse direction [m] l length of raceway contact [m] e Weibull exponent c, h exponents in the stress-life equation. After a time, these stresses cause cracks underneath the surface that gradually extend to the surface. As the rolling elements pass over the cracks, fragments of the material break away. This is known as spalling. Many other failure modes are known, resulting from use in imperfect conditions or installations. ISO 15243 [5] gives a good overview of these failure modes, although, given the latest experience, there is a need for a revision of this ISO standard on rolling bearing damage and failures. In the mid-1950s Arvid Palmgren, a leading bearing theorist, suggested the concept of bearing repair instead of active bearing replacement when he said, “The mean service life is much longer than the calculated life, and those bearings that have a shorter life actually require only repairs by the replacement of the part that is damaged first.” This is not to say that a bearing cannot be used after damage (fig. 4). The presence of damage is identified by increasing noise and vibration levels. Over the decades, repair techniques have been applied to bearings that enabled the restoration of the expected life and reliability of the bearing. Analysis and experience of modern remanufacturing show that refurbished bearings can obtain nearly the life and reliability of new bearings. Considering the extent of rework, results of stress measurement test methods such as XRD [10] (fig. 5) and non-destructive testing methods (NDT) such as the Barkhausen method [11], the micromagnetic testing method (3M), non-elastic wave spectroscopy (NEWS) [12], resonant ultrasound spectroscopy of surface acoustic waves (RUSSAW) testing and phased array ultrasonic analysis gives the representative life factor, LF . The life factor may range from 0.87 to 0.99 of the life of a new bearing (fig. 6). Terms and definitions of reworked used rolling bearings are explained as follows. According to the rate of prior use and the wear status, bearing rework can be divided into five classes (fig. 7). While the operations in the particular classes are numbered, the actual sequence of the work is not directly related to these numbers. Special agreements between the maintenance company and the operator must be respected. Preserving actions between the individual operations may be required. For example, when a bearing raceway is damaged by subsurface-initiated fatigue – see [5] – it is not considered for Class III rework. However, when there is superficial damage (surface initiated fatigue) to the bearing raceways caused by dirt or debris, raceways can often be restored by honing or grinding. For bearing refurbishment (Class II) or remanufacturing level 1 (Class III), repairable bearings are disassembled, the components are visually inspected, and the hardness of the bearing rings is measured. The components that are determined to be restorable are dimensionally inspected. Where necessary, the bearing side faces, bore diameter and outside diameter are ground or polished as permitted by tolerances. Plating with nickel or chrome may be carried out to allow the surfaces to be reground or polished to the original blueprint dimensions. During refurbishment (Class II) appreciable material removal takes place, which removes superficial damage and modifies the stressed material volume. The surface is finished to its original blueprint specification or better. Then, the bearing is refitted with new rolling elements with a diameter equal to the diameter of the elements previously contained in the bearing, plus twice the depth of material removal, if clearance requirements demand it. The new rolling elements must be of the same nominal rolling element diameter but will have a gauge that takes the bearing clearance into account. Cages are inspected for cracks and replated if necessary. If required, the cage is replaced with a new one. Usually, new rolling elements are placed within the cage, and the bearing is reassembled. During remanufacturing level 1 (Class III) deeper grinding of inner and outer ring raceways of larger bearings is acceptable. Moreover, further machining methods (e.g., hard turning) can be applied. Superficial damage is removed, and the stressed material volume is modified. The surface is finished to its original blueprint specification or better. The bearing is then refitted with new rolling elements having a diameter equal to the diameter of the elements previously contained in the bearing plus twice the depth of regrinding. For cylindrical roller bearings, the roller length as well as the roller diameter is increased. The new rolling elements usually exceed the original nominal rolling element diameter. This large increase of the rolling elements may require reworking of the cage pockets or replacement of the cage. With clearly defined procedures and classifications in place, it is possible to ensure that bearing reworking can meet specified standards and comparisons made between service providers. Class 0 includes inspecting used bearings (or bearings that were stored for a long time) and comparing them with drawing/specification requirements. This process involves: Note: Usually a recommendation for appropriate treatment and suitable rework class is given. Reclassification includes all operations of inspection (Class 0) and the following additional work: Refurbishment of bearings encompasses all of the operations of inspection (Class 0) and reclassification (Class I) plus one or more of the following: Remanufacturing level 1 for bearings encompasses all of the previous operations of inspection (Class 0) and reclassification (Class I) and, where appropriate, refurbishment operations (Class II) plus one or more of the following operations: 19) Installing oversize rolling elements of a larger nominal diameter (see operation 13) 20) Installing the original reworked cage or a new one (see operation 14) Remanufacturing level 2 for bearings involves rework of bearings of Classes I to III and encompasses an additional operation. SKF has a global network of state-of-the-art service centres, giving customers access to SKF’s world-class bearing remanufacturing capabilities. SKF is one of the leading global suppliers of bearings, and SKF Remanufacturing Services are backed by more than 100 years of knowledge and experience with rotating machinery. SKF uses the same high-quality materials, methods and machinery to rework bearings that are used in the original manufacture, giving customers the peace of mind that their bearings and related equipment (housings, for example) are being treated with the same level of quality, work processes and knowledge, regardless of where in the world a customer is located. Potential benefits of using SKF Remanufacturing Services include: The full benefits of adopting the remanufacturing programme can be achieved when customers also use SKF predictive maintenance expertise.

Summary

Bearing life and reliability

Subsurface-initiated fatigue

Other failure modes

Consequences

Classification of bearing rework

Further work

Class 0 – Inspection

Class I – Reclassification (requalifying, reclamation)

Class II – Refurbishment (reconditioning)

Class III – Remanufacturing level 1

Class IV – Remanufacturing level 2

Global access