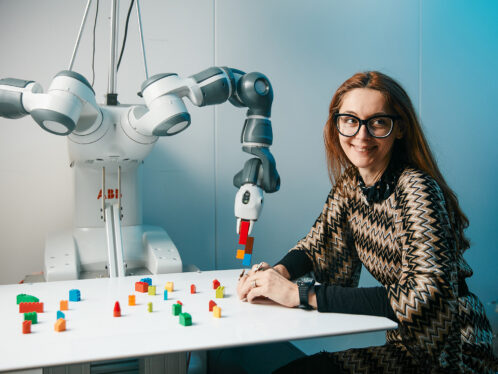

The FABulous Sherry Lassiter

Sherry Lassiter dreams of a world in which almost anyone anywhere can make almost anything. Through the FAB Lab network – 1,200 labs in 100 countries – she is seeing that dream become reality.

The Industrial Revolution changed the world, bringing with it manufacturing, jobs, education and consumerism. It also brought us industry on a massive scale as well as gross inequities in terms of the economy and quality of life and vast environmental problems. Now, the digital revolution is rapidly advancing, and forward thinkers such as Sherry Lassiter, founding partner and director of the Fab Foundation, envision developments that can help us turn the trajectory towards a more equitable and sustainable world.

“The Fab Lab network is considered by many the biggest, most coherent network of makers in the world, due to our relationship with MIT [the Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and our focus on education,” Lassiter says. “We’ve fostered the growth of a network of about 1,200 labs in 100 countries. We’re about making with digital fabrication and about impacts you can make through both new economic opportunities and strong social networks leveraging these tools.” And thanks to the digital-fabrication tools and knowledge that Fab Labs are bringing to the public, anyone can make almost anything almost anywhere in the world.

“Think about the digital revolution or the era when computation came into being,” she says. “We made a small percentage of the population really rich and left many behind. Many in the world still don’t have access to the internet. For them, trying to catch up economically is just not realistic. With the revolution in digital fabrication we have a chance to change that equation if we do it right – and now. How do we democratize access to knowledge and tools in ways that are equitable and allow many people into that economic future?”

“Neil Gershenfeld [founder of the Center for Bits and Atoms at MIT] graciously let me take his course [How to Make Almost Anything] because it would inform my work. I was able to see the early research and applications work going on in digital fabrication and understand that technology is not a black box. That class was transformational. I went back to school for my master’s in education and started the Fab Foundation at the same time. It was an incredibly empowering experience, to become a creator of tech rather than just a consumer of tech.

We see that empowerment happening all around the world in Fab Labs. Once someone creates the technology, they see it has the potential to change lives and change communities.

Sherry Lassiter

“I made this kind of education and access my mission. I didn’t want kids to take 35 years, like I did, to discover that tech can be accessible, meaningful and can change the world in good ways. We see that empowerment happening all around the world in Fab Labs. Once someone creates the technology, they see it has the potential to change lives and change communities. That’s why I’m here doing what I do. I’m very excited and passionate about tech.”

Access to education in emerging technologies at the grassroots level can lift people from poverty and transform economies and cities worldwide.

Lassiter took the principle into physical form by establishing with Gershenfeld the first Fab Lab in Boston in 2003. Since then, Chevron, General Electric and other companies have supported the work with investments of millions of US dollars in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education through the development of Fab Labs across the world.

“At first we had to help the Fab Lab network grow and scale,” Lassiter says. “Our focus now is on social impact. Rather than putting computers in the world, we wanted to put a subset of the work we do at MIT into the communities, asking, ‘If you had access to these technologies, what would you do with that power and opportunity?’ What does the world look like when anyone, anywhere, can make almost anything? There are fascinating implications for education, economic opportunity and social impact. It’s all so new; the workforce of the future looks really different than it has in the past. Technology is bringing vocational and academic pathways back together.”

An evolution in the work has been the Fab Cities project. In Barcelona, Spain, the mayor has plans for 16 Fab Labs, with five now under way. They design and manufacture with local materials in different fields, including furniture, clothing and housing. “It takes the idea of a green footprint and sustainable city to a more interesting place,” Lassiter says. “Rather than import and export goods, why not import and export data and manufacture locally? Rather than shipping materials and products all around the world, they’re trying to do it all locally. That’s a wonderful goal.”

How can one bring a Fab Lab to their town? “If you’re the first in your community, buy a Fab Lab (around USD 125,000) or partner with one to make fab machines for your community, then use that lab to make other Fab Labs. It’s getting close to the point where a Fab Lab can self-reproduce at a tenth the price. If you’re able to rapidly reproduce and prototype manufacturing machines, then your designs are not constrained by the tools that are out there. You just have to manufacture a machine that does what you want it to do.”

Lassiter continues: “Every Fab Lab in the world shares some of the same of tools and processes, but they’re each very different because they respond to their communities and what their needs and interests are. Some focus on tech and entrepreneurship, others focus on issues that are important in their community, like how to preserve and protect water or education or, in Amsterdam, where the arts community wants access to tools for their own personal expression. We’re working with Nike on materials they manufacture with, using digital fabrication to create things that are sustainable and recyclable. Same with the projects we’re working on with the airline industry; we’re thinking hard about materials and manufacturing. We couldn’t possibly think of all the amazing ways you could leverage this technology and knowledge.”