When precision is key

Martin Molin has a grand plan: to perfect the design of his “marble machine”, an innovative musical instrument that plays music through the use of falling steel balls – with a bit of engineering help from SKF.

For the past seven years, Swedish musician Martin Molin has been working on a new musical instrument, something that he calls a “marble machine”, which is playable but is, he admits, completely impractical.

“A guitar is a good tool to make music,” he says. “A midi keyboard is perfect. A marble machine is almost the worst possible solution you can have.”

So why would anybody spend seven years – and counting – to develop such an imperfect instrument? To an extent, Molin says, it’s because he sees the machine more as a piece of art than as a piece of engineering, and in fact he often describes it as a sculpture.

“People still ride horses, despite the invention of the car,” he says. “I want to see how far I can take my horse.”

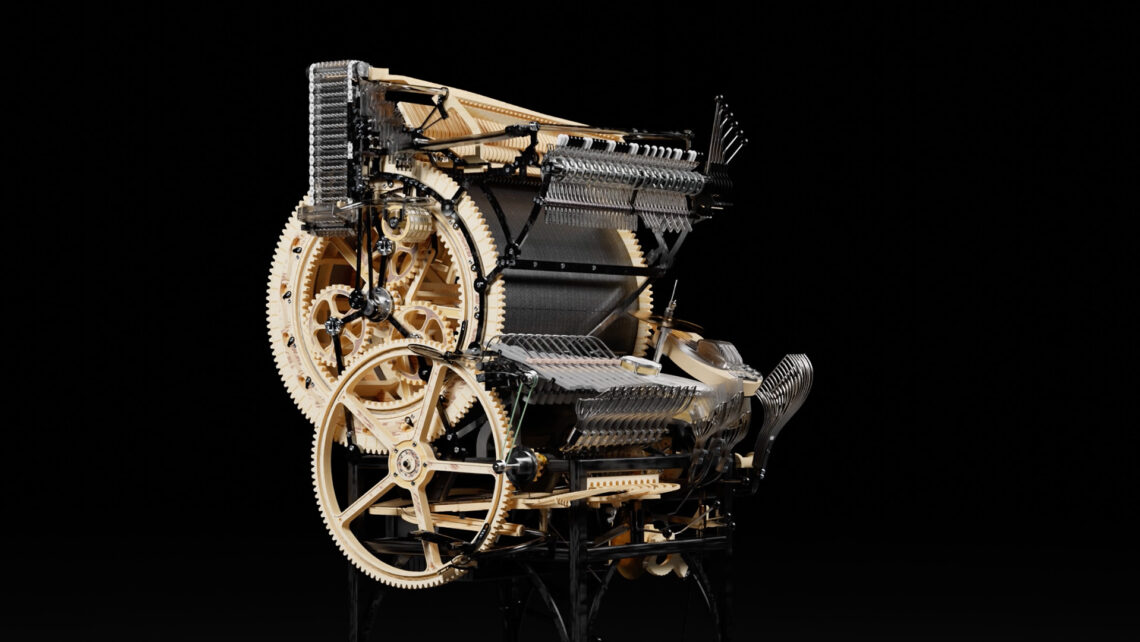

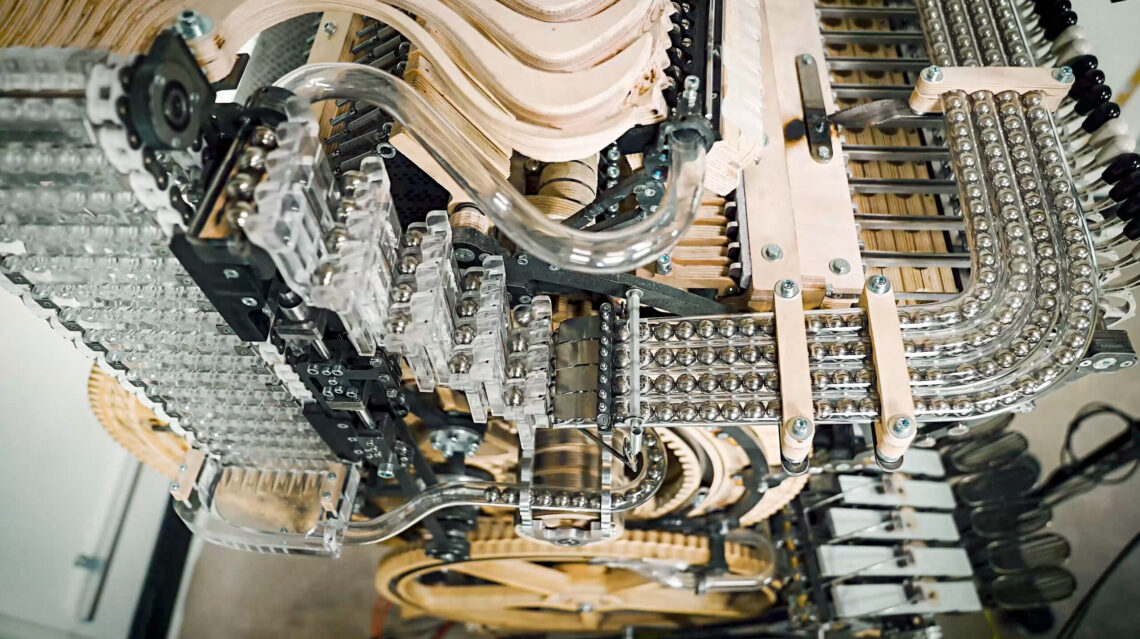

To fully appreciate Molin’s invention, a brief explanation of the marble machine is needed. It resembles a Victorian spinning loom, but one that is filled with 2,000 steel balls, which Molin calls marbles. An early prototype, which he says was built very much on the fly, became an online hit. So Molin created another, more sophisticated prototype, which is operated by turning a hand crank. This lifts the marbles to the top of the machine. From here, thanks to gravity, they fall through various mechanisms. Some of the marbles fall onto vibraphone keys to play specific notes; others fall onto percussion pads.

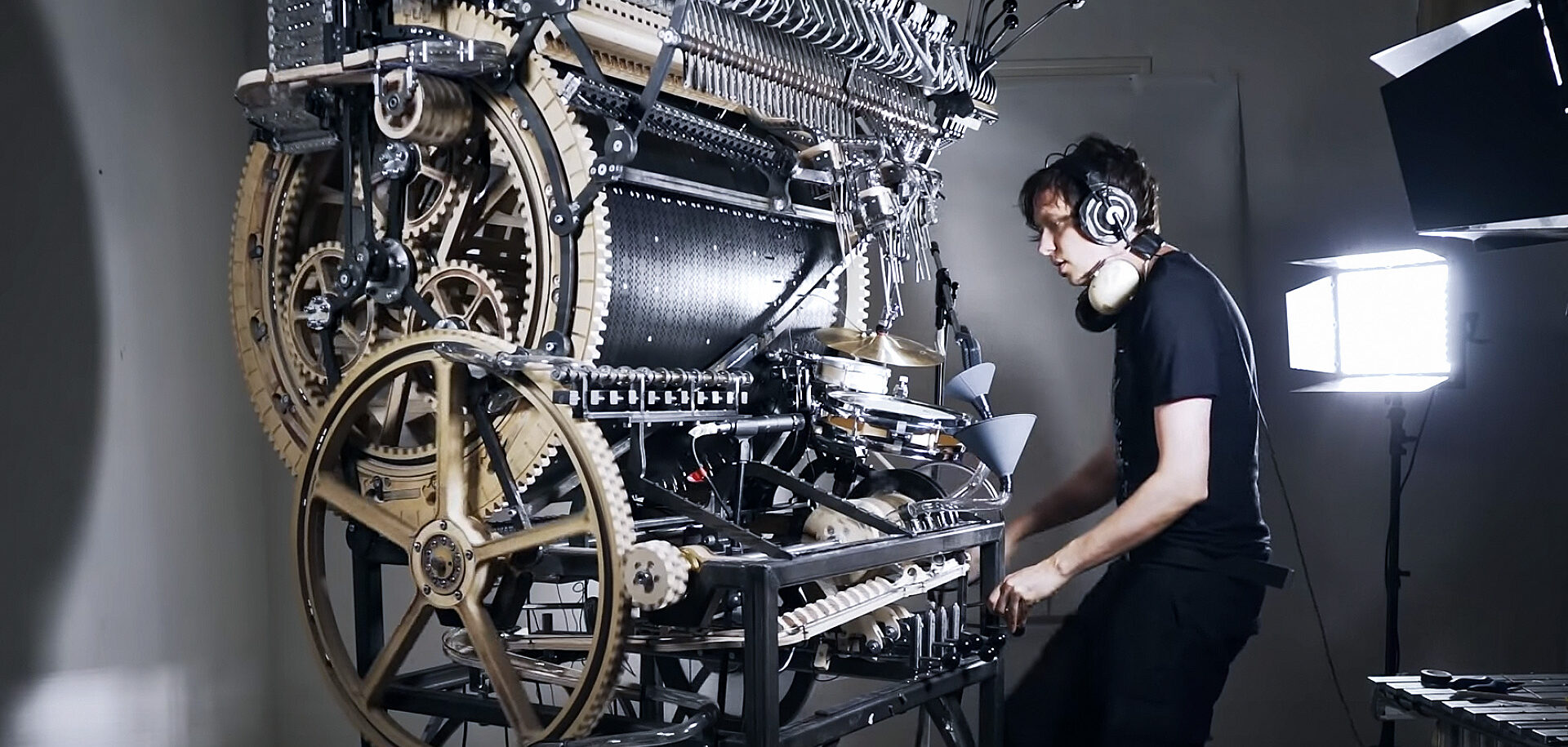

Molin says it is important to be able to “play” the machine, rather than simply to press a button and stand aside. The balls fall into a prearranged musical pattern, with input from Molin to create dynamics. “The music is pre-programmed,” he says, “but if I don’t pull the levers it won’t be dynamic.” Thus Molin can mute certain sections, which allows him to, for example, make changes between a verse and chorus. In addition, part of the machine includes bass strings, which he plays himself.

“There need to be surprises and mistakes,” he explains. “I really want it to be used live, so every concert audience will get a different version of the music.”

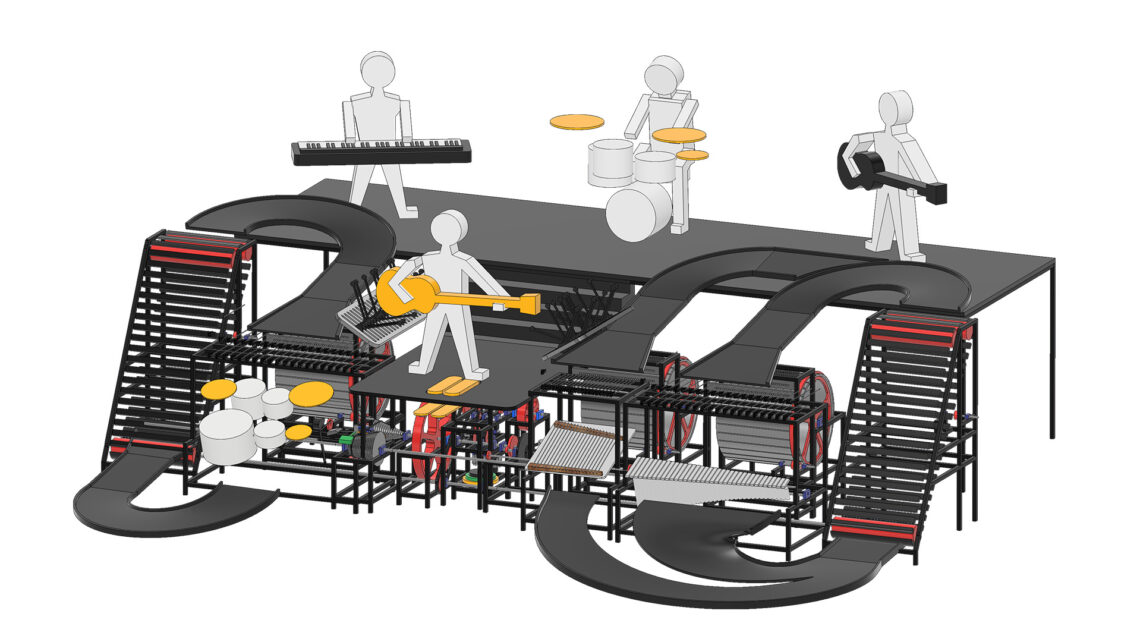

Molin says he has plans to build Version 3 of the marble machine, and when it’s perfected he hopes to incorporate it into his stage show and take it on tour with his band, Wintergatan.

Mechanical music

The marble machine is made from standard parts and is entirely mechanical – no electrical or electronic parts. “I could probably remove 60 percent of the components if I used electric motors,” he says. “But from an artist’s point of view, doing it my way makes sense.”

People still ride horses, despite the invention of the car. I want to see how far I can take my horse.

Martin Molin

The marble machine has distinct similarities to instruments such as the pianola, or player piano, which was popular in the early 1900s. As part of his research, Molin visited two mechanical instrument museums. “These instruments tend to be fascinating for about a minute, after which time people become bored,” he says. This, he explains, is why the inner mechanisms of the marble machine are on show and not encased behind panels. “I want to show the guts of the machine,” he says. “It keeps people interested.”

This also taps into Molin’s feeling that he’s creating a sculpture, albeit one with moving parts that creates music. It’s a balance between art and engineering, an issue that Molin says comes up for him again and again. He admits that he is a novice engineer, but points out that he is learning all the time.

One challenge that Molin faces is the timing of the marbles. To create tight music the marbles must be controlled to an accuracy of one millisecond. “This is more precise than [can be achieved by] a human musician,” Molin explains. For a human musician, a slight variation in timing is considered the “feel” or “groove” or “emotion”, but if something like a drum machine is slightly out, it’s an error.

Engineering rigour

However, Molin says, developing a mechanism that plays music with absolutely accurate timing is a tall order. Part of his journey has been to adopt engineering principles more rigorously – and here he’s turned to SKF and others for help. “One big thing I’ve realized is the importance of reliability,” he says. “The machine must work consistently. I don’t want it to break and let an audience down.”

With guidance from SKF and others Molin is learning the vital engineering principles that will help him perfect his machine. He posts a regular YouTube video, in which he shares his ideas as well as his progress and setbacks. Often viewers will help him solve problems.

The fame that Molin generated through these posts was partly what attracted the attention of SKF. Enter Roger Emlind, an experienced SKF engineer who has become the main link between Molin and the company. He sees himself as both a sounding board and a guide for Molin in the world of SKF products, introducing traditional engineering principles to the unconventional problems the marble machine generates. (More details in the side box.)

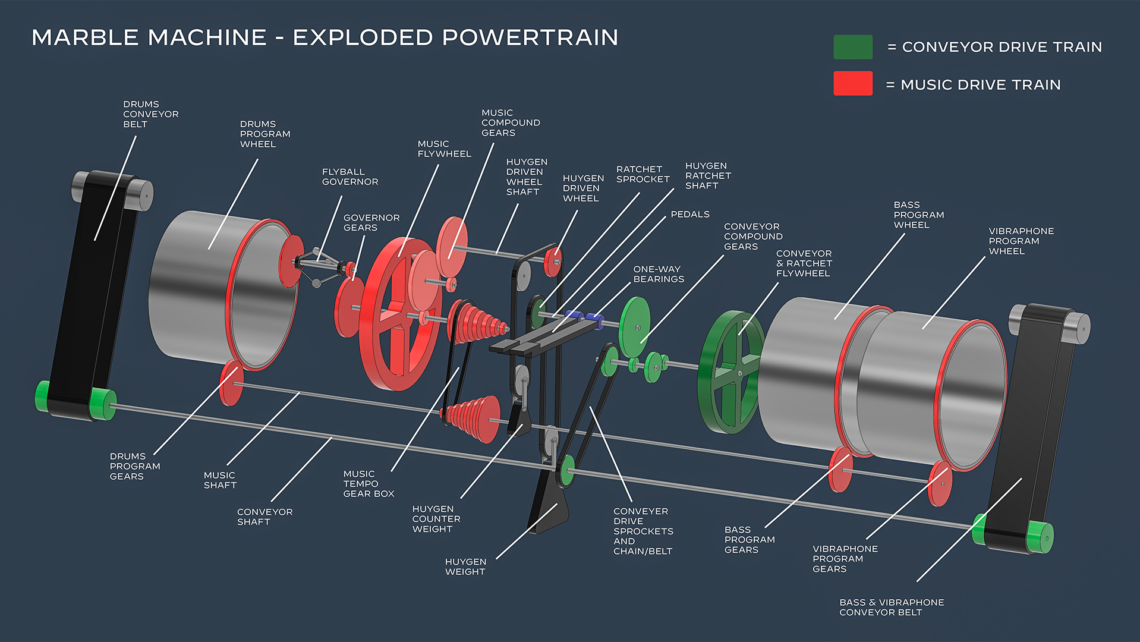

Molin’s somewhat innocent approach means that he stumbles across potentially revolutionary solutions to the problems that come up. One such solution is the Huygens drive, developed by the 17th century Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens. It was devised as a weight-driven way of powering clocks and helping old telescopes track stars across the sky. “I’m planning on using the Huygens drive to smooth out power input using gravity,” Molin says.

He is also using two large flywheels instead of the hand crank to regularize the flow of marbles through the various parts of the machine. “An interesting part of the timing is the ability to rotate a single shaft with very precise rpm,” he says.

Among other things, Molin is working constantly to refine the design of the gate that releases marbles according to demands of the pre-programmed music. And he seems to have something of a love/hate relationship with the ‘marbles’ – which he says are prone to “misbehave”. The degree to which they can do evil has surprised me,” he says. “They are basically chaotic and want to wreak havoc. That’s what I feel ready to solve in Version 3.”

The finale

Version 3, Molin says, is meant to be the final version of the marble machine. There is no working model yet. At this point he is working out how to refine the separate parts, such as the flywheels and the Huygens drive, and to introduce foot pedals instead of a hand crank, to have both hands free to play the machine.

In addition, Molin has begun using 3D CAD modelling to design various elements (although he is quick to add that 2D pencil and paper also have a key role).

Despite the seven years Molin has put into the project, he remains enthusiastic about it. Still, though, he is eager to reach the end. “I want to finish the machine in order to show what happens if you don’t give up on your dreams,” he says.

Help behind the scenes

Roger Emlind has many years of engineering experience at SKF – and before that, at SAAB – but working with Martin Molin, he says, has been an entirely new experience.

“He’s not your normal machine designer,” Emlind says. “He possesses an eagerness to learn and is open to his flaws.”

Molin’s “art first” vision required an untraditional approach to machine design, and for Emlind, who is more used to dealing with trained engineers, this meant that the bearing engineering needed to be done implicitly.

Since SKF has been on board, Emlind’s main role has been to respond to Molin’s requests for insight and guidance. Part of this included recommending appropriate SKF products.

“The process of selecting the products probably took a few minutes,” he says.

Other than the marbles, which are standard SKF steel balls, Version 3 of the machine will use several SKF products, including sprockets, chains, Y-bearings and bushings. The Y-bearing helps Molin to position a shaft accurately and easily using just two bolts. The bushing allows for a simpler shaft design and more generous shaft tolerances when attaching a shaft to the flywheel, and at the same time it secures the positioning and minimizes vibration.

As well as helping to select products, Emlind has also provided expertise and rigour to the process – for example, when he carried out detailed calculations on the Huygens drive. “I wanted to see if there was a way the system could be misconfigured,” he says. “These are the kinds of questions that an engineer needs to ask.”

Even though Molin is new to the world of engineering, Emlind says he was “blown away” by Molin’s persistence and his willingness to share his challenges.

“The whole marble machine project is a really interesting and beautiful combination of art and engineering,” he says. “That’s why I was intrigued.”