Dead Sea alive with mining activity

The Dead Sea is proving to be a rich source of minerals, including potash. The Dead Sea Works is using a method developed by the company to mine these minerals and export them to the world at large.

Summary

SKF’s relationship with Dead Sea Works and its parent company Israel Chemicals dates back to when SKF was DSW’s primary bearing supplier and also provided close engineering support through its Israeli distributor Muller & Co. Due to demanding applications and the extreme environment, DSW’s need to find ways to optimise its equipment is ongoing.For example, compactors at the potash granulating plant work in very severe conditions. Bearings run under a heavy load of C/P < 2-3, at a low speed of 18 r/min in ambient temperatures of more than 50 degrees Celsius. Meanwhile, potash is highly abrasive and will damage components quickly. The result was frequent and costly downtime.Working together, SKF and DSW initiated a solution based on improved lubrication and cleanliness. Grease with higher viscosity was selected, which improved performance and also resulted in better contamination exclusion. This resulted in considerable service-life improvement.Over the years SKF has continued to work closely with DSW to improve compactor mean time between failures (MTBF). And, since maintenance practices are critical, SKF introduced the use of SKF SensorMount®, which enables accurate and fast mounting of the large bearings of the compactor. As a result, MTBF increased by three to four times.DSW also implemented a condition-monitoring programme based on the Microlog® and is now able to detect pending equipment failure far earlier. This programme helped DSW reduce the mean time to repair (MTTR) by almost half.

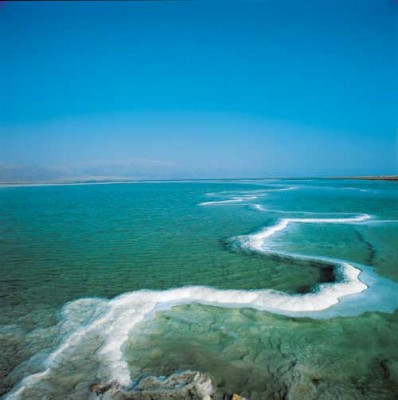

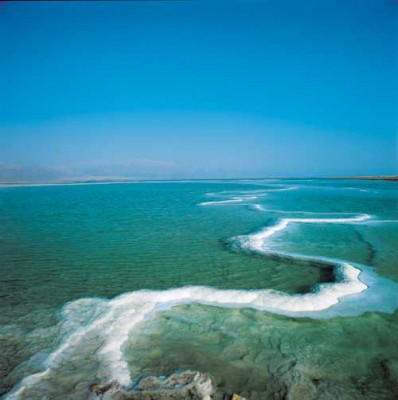

By its name, the Dead Sea hardly conjures up a sense of prosperity. In Biblical times the desert region, known in Hebrew as the Salt Sea, was largely isolated. The harsh climate, with summer temperatures reaching 45 degrees Celsius in the shade, has made the area largely uninhabitable. But in modern times the Dead Sea, the lowest point on the earth’s surface, has turned into something of a gold mine, its mineral-rich waters producing billions of dollars’ worth of chemicals.

Located at the southwestern corner of the Dead Sea, just 10 kilometres past the ancient fortress of Masada, is one of Israel’s largest industrial complexes. It is owned by Israel Chemicals (ICL), a leading international chemical firm. More than 3,000 industrial workers are bussed in daily over distances of up to 100 kilometres to work at the huge complex. Potash and magnesium chloride are produced at the site from the highly saline waters of the sea, which straddles the border between Israel and Jordan. The riches of the sea have turned Israel and ICL’s Dead Sea Works subsidiary into the world’s fourth largest producer of potash, a leading fertiliser.

Unique method

In most parts of the world, potash is mined. But Dead Sea Works (DSW) has developed a unique method of extracting the mineral from seawater. The technology is based on the use of evaporation ponds that take advantage of the region’s high temperatures and low humidity. The average annual temperature is 35 degrees Celsius, and rainfall amounts to only 50 millimetres a year. Even in the winter, daytime temperatures rarely fall below 20 degrees Celsius. “The climatic conditions at the Dead Sea enable us to harness the sun and make use of the high level of evaporation to produce potash,” says Oded Harel, manager of operations and process engineering at DSW.

The Dead Sea mining area is crisscrossed by 2-metre-deep evaporation ponds. Each pond is about 6 square kilometres in size, and the ponds are divided into two categories: salt ponds and carnallite ponds. The latter form the basis for the production of the potash.

The salt ponds hold the brine that is not needed in the industrial production process. The carnallite is removed from the harvester ponds by a raft-like harvester developed by DSW. Manned by two-member teams, the harvesters are connected to the shore by a network of cables that allow them to manoeuvre between the various ponds.

The process itself works by suctioning carnallite-rich slurry through an intake valve. The harvester then pumps the slurry into a series of floating pipes that run along the surface of the carnellite ponds to the shore. Two plants based on cold and hot leach-crystallisation processes decompose the carnallite and turn it into potash. The production process continues 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The entire cycle from the harvesting to the actual production takes only five hours.

Potash in grades

“We produce three different grades of potash, and each one is earmarked for a different segment of the market,” says Eyal Yaffe, DSW plant manager in charge of compacting and logistics. The standard potash, easily recognised by its large crystals, is used for direct agricultural applications. It is primarily used in developing countries where potash is distributed by hand. The thin-crystal potash is used for the production of downstream products. The third grade, called “granulated,” is used in the bulk-blending of potash and is produced using a compacting process.

Once production is completed, the potash is stored in huge piles that are clearly visible at the entrance to the extensive complex. “The climatic conditions allow us to store material outside and ship it as market conditions warrant,” says Eli Amon, DSW sales manager. He adds that the size of the potash piles is a clear indication of the state of the market. These days the piles are very low. With a very tight market, potash is shipped out through Israel’s southern Red Sea port of Eilat or the Mediterranean port of Ashdod within a matter of days following production.

“More than 90 percent of our Dead Sea production is exported to about 60 countries in all parts of the globe,” says Amon. The company’s biggest markets are Brazil, China, India and Western Europe. Demand for potash is growing at 2 to 3 percent a year. However growth in demand in Brazil and China is more than double that.

The annual world production of potash is around 45 million tonnes. Israel ranks fourth, after Canada, Russia and Germany. The DSW plant currently produces 3.3 million tonnes of potash annually. The Dead Sea plant is currently producing at full capacity, due to the strong demand worldwide for potash. Over the years the plant has been continuously expanded and is now in the process of increasing production to 3.6 million tonnes. In addition to its plant at the Dead Sea, Israel Chemicals produces 2 million tonnes at plants in Spain and Britain, where the potash is mined using traditional methods.

The Dead Sea has another major advantage. Unlike mines around the world it has an almost unlimited supply of potash. “There are enough minerals in the waters of the Dead Sea to last for more than a thousand years,” predicts DSW operations manager Harel. With those kind of reserves, the Dead Sea will continue to help feed the world’s growing population for centuries to come.

A family affair

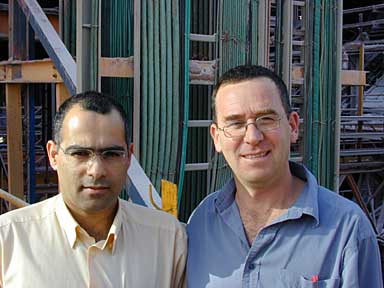

Natan Besser’s day begins at the crack of dawn. By 6 a.m. he catches a company bus that picks up workers in Dimona, a town 45 kilometres from the Dead Sea Works. The ride down the winding road leading to the Dead Sea takes just under an hour.

By the time he gets there, the heat is already intense. After suiting up, Besser and his team of 14 workers hop into 4X4 vehicles that take them to the ponds. Two-man teams operate each of the five raft-like harvesters that collect the carnallite that serves as the basis for the production of potash. The other four provide services to the operators.

Besser says that despite the harsh conditions, things have gotten easier over the years. Nowadays everything, including the harvesters, is air-conditioned, he says. But the work schedule is tough. With round-the-clock operation, workers have 12 days on the job and four days off.

But “the company,” as he calls DSW, is sort of a family affair for Besser. His father worked there for 28 years and seven years ago his son joined him. Besser sees DSW as a great place to work and says the company takes care of its workers. “If this weren’t the case, you wouldn’t find so many second- and third-generation family members working here,“ he says.