Maximum velocity

Dallara Automobili has been described as “the most successful racing car builder of modern time.” What’s its secret?

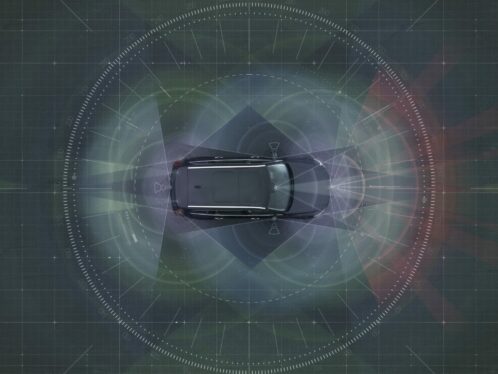

Engineer Gian Paolo Dallara has never been afraid of speed, on or off the racetrack. Quite the contrary: He built a company by seeking it out. Today, Dallara Automobili is “the world’s largest, most influential and most successful racing car builder of modern time,” according to Motor Sport magazine. Although the company’s reach is global, its roots echo those of its founder, who was born a few metres from the company’s current headquarters in Varano Melegari, near Parma in northern Italy – and he still lives in the same house. Gian Paolo Dallara earned his engineering degree from the Politecnico di Milano in 1959. Before graduating he spent two months in Gothenburg, Sweden, in an apprenticeship at SKF. The experience served to improve his English and introduce him to SKF’s corporate culture. “I saw how they worked,” he says, “and since then, bearings and SKF are synonymous in my mind. Throughout my career, whenever I had a choice among components, I saw that it always paid to choose the high-quality option.” Quality has been a hallmark of Dallara’s own career path. After graduation, he started at Ferrari in the technical department. Here, his nascent passion for car racing was fanned, and three years later he followed it to Maserati. His first job there was to follow the Cooper-Maserati Sebring 12 Hours. The drivers were racing legends Bruce McLaren and Roger Penske. He remembers the experience as “fantastic” but he wasn’t spending all his time on racing, and that’s what he wanted to do. When Lamborghini approached him in the mid-1960s to become its technical director, he jumped at the opportunity. His time at the company resulted in one of the car projects of which he remains most proud, the Miura. However, while Lamborghinis were avant-garde and technically fast, they were not dependable performers on the track, “and you need that to win races consistently,” Dallara explains. So he went to De Tomaso Automobili, founded by Alejandro de Tomaso, whom Dallara describes as “a born salesman”. Soon after, Ford bought out De Tomaso, and the company withdrew from racing. At this point, in 1972, Dallara started his own company. “If I couldn’t work in racing full-time for someone else, I would do it on my own,” he says. His first office was his father’s garage, his first hire was a local mechanic and his first client was Lancia. He worked as a consultant on the Lancia Stratos rally car, which led to other racing projects. One success generated another, and within six years he was building cars for the Formula 3 series. The company’s fame spread across the continent, but it was not until 1993 that Dallara conquered the UK – the heart of commercial racing car production. A Dallara performed well in a British Formula 3 race in April of that year, and within three months nearly all cars on that circuit were equipped with Dallara chassis. In 1996, when the Indy Racing League was formed in the United States, Dallara saw his opportunity to crack that formidable market. The company faced heavy competition from an American competitor. In addition, Dallara admits, “Our cars weren’t performing as well as we wanted.” In the space of a few months, the company made a number of modifications and gave away the improved pieces for free. By acting quickly, the company retained its customers’ trust. Today, Dallara builds chassis for eight car championship series: Indycar, GP2, GP3, World Series by Renault, Formula 3, Indy Lights, Grand-Am and German junior series Formel Master. These represent 60 percent of its turnover; the rest comes from consulting for racing and automotive engineering. The latter is a growing area, in part thanks to investments such as a new wind tunnel and an 8-million-euro, Star Wars-like driving simulator, inaugurated in December 2010. Dallara’s chosen successor in the privately owned company is Andrea Pontremoli, who was CEO of IBM Italy before assuming the direction of Dallara. Like the company founder, Pontremoli has local roots, a love of racing and a desire to keep faith with customers. A racing car has no guarantees because of all the factors at play in competition, observes Dallara, “so our clients have to feel confident in what we are doing. What accounts for our success is that our definition of quality is client satisfaction.” For the eight championship series in which Dallara cars compete, SKF has introduced sophisticated solutions that one normally finds only in Formula 1 cars. The bearings used by Dallara represent the best combination of performance (maximized stiffness, minimal friction, optimal lubrication) and bearing life. The most critical bearings are produced by the SKF Racing Unit; each bearing has a unique serial number to ensure traceability, underscoring its reliability. Because the SKF Racing Unit is focused on its clients’ need for performance on both the finish line and the bottom line, its partnerships result in the most effective and efficient solutions. As Fabio Falsetti, SKF Racing Unit product manager, explains, “We supply four wheel-bearing types to cover the needs of all cars in the eight championships. This lowers Dallara’s inventory costs but not its track performance.” SKF at the racetrack