Shock of the new

With the business world rapidly evolving, accelerator and incubator schemes promise large corporations a way to keep pace with innovation while supporting tomorrow’s industry leaders.

We live in an age in which established industries are constantly being disrupted by new technologies and innovations. Uber has turned the global taxi industry on its ear, Airbnb has disrupted the hotel sector, and Netflix’s media production model is challenging both television networks and Hollywood filmmakers.

What can today’s large corporations do to ensure that they keep pace with disruptive technologies and that their employees have relevant skills? An increasingly popular approach is for businesses to actively expose themselves to innovation by developing connections with promising start-up companies. Working through business “accelerator” and “incubator” programmes, corporations send staff members to work with the leaders of budding new companies, providing them with strategic advice, mentorship and, in some instances, seed capital. In return, the corporates may get a share of a successful new business and, perhaps most importantly, exposure to new ways of thinking and new technologies.

The start-ups themselves get access to potential customers and strategic investors, as well as senior industry and management expertise.

Ian Hathaway

Corporations that become involved in start-up programmes get what consultant Ian Hathaway calls a “front-row seat to the frontiers of innovation”. Hathaway, a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, one of the US’s leading think tanks, says, “They’re exposed to the start-up way, which can enhance company culture, and they can diversify and improve upon their corporate development and innovation efforts. The start-ups themselves get access to potential customers and strategic investors, as well as senior industry and management expertise. They also have access to markets and suppliers that would be difficult to secure on their own. So there are benefits both ways.”

While definitions vary, Susan Cohen, assistant professor of management at the Robins School of Business at Virginia’s University of Richmond, says both incubators and accelerators offer start-ups a forum where they can develop their business. However, while incubators tend to offer long term-programmes of up to five years, the focus within accelerators is on a fast turnaround with a fixed-term programme often culminating in a “demo day”. Both incubators and accelerators can be independently run, government-sponsored or positioned within companies.

The prevalence of both types of organization is growing. A report published in 2017 by funding platform Gust found the number of accelerator programmes globally had grown by 50 percent to 579 between 2015 and 2016, and the number of start-ups involved stood at nearly 9,000. Some 206 million US dollars were invested in the schemes.

SKF Innovation Challenge

More than 80 start-up companies applied to take part in the project, and after a selection process 14 of these were selected to take part in a mentorship programme with SKF. Finally, four start-ups were rewarded. But the main take away is the connection created between the start-ups and the “big company” thanks to this challenge. Today, Proofs of Concept (POC) have been initiated with six start-ups: four proposing solutions on machine learning, one on detection of quality processes and one on monitoring energy consumption.

Often cited as the first accelerator, California-based Y Combinator is also among the best known; since being established in 2005 it has helped now-global names such as Dropbox, Airbnb and Reddit find their feet. Other big-name accelerators include Techstars – which has programmes involving Amazon, GE and Ford – and PlugAndPlay.

Cohen says that while accelerators are often associated with software and IT, the concept can work in just about any sector. “We see them in a broad array of industries, including energy, food, retail, telecom, automotive and health care,” she says.

On the incubator front, California-based Idealab and New Zealand’s The Icehouse have both helped thousands of entrepreneurs build their businesses.

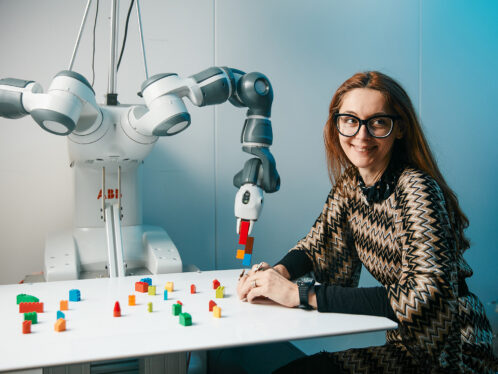

In Sweden, technology giant Ericsson, a global ICT solutions company, is an example of a business that is proactively working to foster a culture of innovation by working closely with start-ups. In 2014, the company established Ericsson Garage, an “open-innovation platform” that founder and head Sandor Albrecht describes as a cross between an accelerator and an incubator. In 13 locations in North America, Europe and Asia, the various Garages are forums where employees can take time out to work on new business ideas. Each year, the company also works directly with a handful of start-ups, putting them through a six-month programme that involves mentorship, training and contact with the company’s sales force and customers.

Albrecht says that with Ericsson focused on the possibilities around 5G telecommunications technology, the contact with start-ups opens the company’s eyes to situations and opportunities it might otherwise have missed. “One of the start-ups in our incubation programme this year is Build-r, a small Swedish start-up that wants to disrupt the construction industry by building and selling a robot that can install drywall,” he says. “We would never, ever have come up with a use case like this, and it shows just how innovative the 5G platform can be.”

Hathaway says he believes accelerators tend to provide better results for the start-ups involved, largely due to the accelerated time frame in which the companies progress.

“In general, there is good evidence that accelerators are achieving their stated aims, such as increasing the ability of accelerated companies to raise a round of venture capital and acquire customers and other key growth metrics,” he says. “But it’s important to know that not all accelerators are effective – many may have no impact at all and some may even be harmful. Quality matters.”

The evidence on incubators is murky. For example, the Kauffman Foundation did a literature review of more than 30 studies and couldn’t find conclusive evidence that incubators had a positive influence on start-ups.”

Cohen, meanwhile, warns that simply connecting with a start-up won’t ensure business success. She also believes that many established businesses will find other ways of retaining their position as technology evolves. “There are many innovations that are not disruptive for incumbents,” she says. “For example, it’s looking like electric vehicles may not disrupt the automotive industry. Sure, it’s a big innovation, but that doesn’t always mean that it’s a disruptive one.”

However, Hathaway stresses that it’s crucial for established companies to remain up to date with market trends. He points to the often-cited case of the film company Kodak, once an industrial giant with operations across the globe. Unable to see the potential of emerging technologies, the business stuck to its tried-and-tested business model and was largely obliterated by the rise of digital camera. “Companies that don’t look for ways to remain abreast of disruptive culture and new innovation risk going the way of Kodak,” he says.