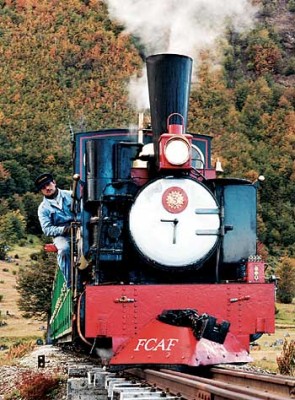

Train at the end of the world

The journey to the end of the world is about to extend an additional nine kilometres.

Summary

The Train at the End of the World currently uses a combination of brass bushes and roller bearings on its two steam and three diesel engines, and roller bearings throughout on its passenger cars and freight-carrying wagons.

Steam engine Camila, for example, uses 18 SKF bearings:

- two on the axle boxes of the front carrying wheels

- six on the axle boxes of the six driving wheels

- two on the axle boxes of the rear carrying wheels

- four on the valve gear

- four on the main driving rods.

Part of Technical Manager Shaun McMahon’s action plan for the future is to replace the remaining brass bushes with standard roller bearings from start to finish, eliminating the need for “oil-can jobs.”

“Brass bushes are really last century’s technology,” explains McMahon. “They may be nice to the traditionalist if you have the resources to deal with them, but we haven’t. Remember, we’re at the end of the world here.”

Three shrill blasts from the whistle of a steam engine shatter the stillness of a chilly Patagonian morning and send a ripple of excitement through a crowd of tourists sitting impatiently in quaint wood-lined railcars.

“Here we go,” giggles Milca Chiavarina, 67, a tourist from Buenos Aires, as the Train at the End of the World begins its slow journey into Tierra del Fuego National Park. The tracks trace the final six kilometres of a route that a century ago brought hardened prisoners on open flatbed trains to cut wood – part of the official plan to settle the remote town of Ushuaia, eight kilometres away.

Today, fields of grey, gnarled stumps serve as eerie monuments to the hundreds of tough convicts who chopped trees under the watchful eyes of armed guards. The Prison Train, as it was called, ran from 1896 to 1947.

“The father of a friend of mine used to be a guard here,” Chiavarina says. “I can just imagine him yelling orders at the convicts from one of those hills.”

Tourist magnet

The train still plays a key role in the future of Ushuaia, the world’s southernmost city, where tourism remains one of the few growth industries amid a wrenching economic crisis. Some 100,000 visitors flock annually to the city, and almost half of them take the Train at the End of the World.

“It is really a lovely ride,” says Spanish tourist Francesc Gomez, 28. “The scenery is beautiful.” Although the ride is relatively short, it takes passengers through valleys spotted with grazing horses, rivers filled with upland geese and forests covered in green moss – all set against a backdrop of majestic snow-covered mountains. Tickets cost 54 pesos (18 Euro) for the average tourist, 18 pesos (6 Euro) for children, 72 pesos (23 Euro) for first class and 126 pesos (41 Euro) for a “special” car, which includes cafeteria service for eight people. The train is in operation 365 days a year.

“We’ve had several presidents ride on it,” says Marcelo Lietti, general manager of Tranex Turismo SA, “and authors such as Ernesto Sabato and the Argentine tourism secretary, who had his honeymoon dinner in a presidential car.” This railway development company owns and operates the Southern Fuegan Railway or Ferrocarril Austral Fueguino, as the train is officially known.

The two steam engines and three diesel engines that make up the Train at the End of the World fleet have ferried tens of thousands of tourists ranging from Buddhist monks and Canadian businessmen to American pensioners, often in harsh, snowy weather.

Many of the passengers seem more enchanted with the trains than with the Patagonian countryside. A few turn out to be retired steam engine engineers themselves, nostalgic for bygone days at the head of their own trains.

“I’ve let one or two have a turn at the throttle, and they were so moved you could see the tears come to their eyes,” says Shaun McMahon, technical manager and troubleshooter.

Encouraged by a 70 percent increase over 2001’s earnings, train owner Tranex Turismo SA is now planning to lay an additional nine kilometres of track to bring the picturesque steam engines straight into town where 140 cruise ships dock annually.

“The idea of travelling to the end of the world is enormously attractive today, and people request it constantly,” says Lietti.

It wasn’t always that way. When Tranex Turismo first began operating the line in 1994, income from ticket sales was quickly used to repair and recondition the trains. Along the way Tranex received the help of corporate sponsors, such as Argentine gas company YPF, which supplies free diesel oil for the locomotives. Credit card firm Visa has granted them discounts, and telecommunications giant ATT supplies them with materials such as postcards and tickets.

“It’s only in the past two years that we’ve been able to breathe a little easier in terms of finances,” says Lietti.

Now the challenge is to bring the trains into Ushuaia, which will not only make the journey more interesting but also will increase access to cruise ship passengers, many of whom are elderly. In addition to laying the new track, the project involves designing and building a 21st century steam engine that will be custom-made for the job.

Modern components

“We want this engine to incorporate the latest proven developments in steam locomotive technology,” says technical manager McMahon. Bespectacled and soft-spoken, McMahon began working with trains as a carriage cleaner in Wales at the age of 13 and by the time he was 14, he had already driven his first engine around the works yard.

McMahon can rattle off the specifications and needs of any of the five engines now operating on the line. But to non-experts, the cab interior of a steam engine is an intimidating combination of switches, dials and knobs.

“It took me about two months to learn the fundamentals of driving a steam engine, but I don’t think I’ll ever learn all there is to know,” says Argentine driver Avelino Gonzalez as he poses for tourists beside his engine.

The task before technical manager McMahon today is to fine-tune his existing engines and rolling stock, so repairs can be kept at a minimum. “What we want is trains running in 2002 conditions with 2002 components off the shelf,” concludes McMahon. “It will make it all easier.”

Just as the train will continue growing in future months, the town it calls home is also expanding. Between 1991 and the present, Ushuaia grew some 70 percent to its current population of more than 50,000 inhabitants.

“Ushuaia is a rapidly growing town, and Tranex Turismo is a rapidly growing company,” says McMahon. “They go hand in hand and complement each other in every sense of the word.”