Summary

Remote analysis online

The preventive maintenance system used by LKAB was delivered by SKF. Lars Wendleman of SKF says that each of the five mills in ore concentration plant No. 2 in Kiruna is equipped with 15 sensors. The positioning of these sensors was determined by SKF in cooperation with the customer – LKAB. The sensors send information about the vibrations of the bearings, measured both in terms of speed and acceleration.

Via cables and three local monitoring units these measurements are then passed on to a Windows NT-based computer system using the SKF’s PRISM software. LKAB’s maintenance engineer Roger Johansson analyses all the incoming data and fault indications, if any.

The contract between SKF and LKAB also includes Como Link, which gives Johansson the opportunity to contact SKF via a modem so that both companies can work together online to analyse possible faults. LKAB’s aim is to identify and address all faults before a breakdown occurs. It has succeeded in this in the six years the maintenance system has been in operation.

The next stage in the maintenance programme is to connect the system to the oil pumps in the ore concentration plant. This will involve the delivery of more high-tech products from SKF. But there will always be a human behind all the technology and in this case it will be Johansson at LKAB who decides whether the system is working or not, says Wendleman.

While competitors get their iron ore from open cast mines, Swedish LKAB must mine its ore from deep within the earth. High-tech production is the key to staying competitive.In Kiruna, 250 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, almost as far north as one can go in Sweden, can be found one of the world’s most modern mining operations – that of LKAB. The company is the European Union’s only significant producer of iron ore today. Some 80 percent of production goes for export. But there’s stiff competition on the world market, and in some ways producers in South America, Australia and Canada operate under better conditions than does LKAB.

While their competitors can scoop up vast quantities of ore from open cast mines, LKAB has the painstaking task of bringing it up from the deep underground. The extra work means, of course, extra costs, and because labour in Sweden is relatively expensive anyway, this adds to production costs and reduces competitiveness. Transport is also expensive north of the Arctic Circle, where distances are long.

For these reasons LKAB has concluded it must continue to focus on having the right products, high technology and an effective production.

For LKAB, the right products mean total concentration on processing. The company’s target is that 80 percent of its ore be processed into pellets of various qualities, compared with the 40 percent that went into pellets in 1980. That target is not far off – it is already up to some 70 percent. In addition to pellets, the company believes that fines, sometimes known as sinter fines, in the form of low-phosphorus ore, are going to be important in the future. High phosphorus ore, which today accounts for only a tiny proportion of output anyway, is likely to disappear completely from production.

LKAB has invested in technology and effectiveness, both above and under ground. In the mine itself, it has introduced the remote-control operation of drilling rigs, transportation and loading. Above ground, it has made large investments – both in new ore concentration and pelletising plants and in the takeover by its subsidiary MTAB, MalmTrafik AB, of the transportation of ore to the ports of Narvik in Norway and Luleå in Sweden.

Focus on processing

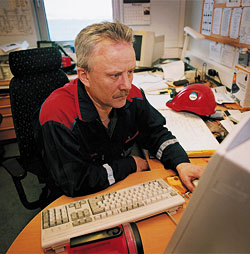

Today LKAB describes itself as a high-tech ore processing company, rather than just a mining company. But this doesn’t make it any less dependent on the skills of its employees – in fact, the reverse. When production is conducted on the “just in time” principle, there is no margin for error, either by people or machines. Everything from extraction to delivery has to function seamlessly for the targets that have been set to be reached. Roger Johansson, a maintenance engineer at the ore concentration plant in Kiruna, is an embodiment of the fact that high technology demands highly skilled personnel.

“The days are long gone when a maintenance engineer went round the machinery listening for faults with his ear to a screwdriver,” says Johansson. “We’ve put the screwdriver away and nowadays we sit in front of a computer screen to analyse what’s going on.”

Johansson’s job is to make sure his machinery doesn’t break down, as a breakdown could have dire consequences for the whole production process in Kiruna. Maintenance takes place, if at all possible, during one of the two weeks that the plant shuts down every year for this purpose.

“My job is to save LKAB money,” says Johansson. “The cost of a breakdown has been estimated at some 120,000 SEK an hour (12,000 USD). The cost over and above that, in terms of loss of goodwill from customers and possible damages, is more difficult to calculate in terms of hard cash. But however you reckon it, it’s clear that a breakdown would cost the company a lot of money.”

Johansson doesn’t exactly fit the popular image of a computer operator, sitting as he does with blackened face and hands in dirty work overalls and boots in front of his screen in a cramped little office, his helmet on the desk beside him.

“It’s not quite that clinical working environment you sometimes see on television, with men and women in pristine white coats in front of their computers,” he says, laughing.

In the ore concentration plant, everything is covered with a thick layer of black dust from the ore. Johansson has just had to change to a new computer keyboard because the dust had clogged the old one up. The computers themselves seem to work perfectly despite their grubby appearance.

A feel for vibrations

You could say that everything revolves around Johansson in the LKAB ore concentration plant – because the bearings are what really count. Johansson can keep an eye on the vibration levels of the bearings in the plant’s five large mills by means of the computerised maintenance system.

“The bearings are the heart or the nerve system of a machine,” he explains. “You can tell a lot about the state of the machine as a whole by looking at the condition of the bearings.”

But it’s not enough just to turn the computer on and put your feet up and then let technology get on with the job. It’s when the system shows that something might be wrong with one of the bearings that Johansson’s job really starts. He must analyse what all the graphs and figures on the computer screen mean, finding the fault and decide what measures need to be taken. The system allows for the most minute checks and analysis of every part of a machine.

Johansson puts on his helmet and takes us out on a tour of the plant that it is his job to supervise. This is the reality behind what can be seen on the maintenance-system computers: five giant-sized mills, which grind the ore into a fine powder. Here and there you can see the sensors that send information about vibrations and rev counts to Johansson’s computer.

The ore we are watching being processed is destined for a ship that is currently steaming towards Narvik for loading. It is always the customer who comes first. As the ship makes port, the train carrying the ore will also be arriving in Narvik. Everything has to run smoothly.

And things do run smoothly at LKAB. In the six years that Johansson has been working there as a maintenance engineer, he has been able to avoid even a single breakdown the last six years with the help of the present computerised maintenance system. So pleased is the company with the system, it has now decided to extend it to take in the oil pumps at the plant as well. Reducing maintenance downtime to one week a year is also being considered.

Leif Åström

a freelance journalist based in Lund, Sweden

photos Erik Holmstedt and LKAB