Waste warrior

Veena Sahajwalla’s enthusiasm for waste has contributed to increased efficiency and sustainability in the steel industry.

Old car tyres, discarded nut shells and empty plastic bottles are just rubbish to most people. But Veena Sahajwalla sees in them potential raw material for use in the making of steel and other value-added products. Sahajwalla is a materials engineer and the director of the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology at Australia’s University of New South Wales. She has helped transform the steelmaking industry in Australia by inventing a steel production process in which old car tyres and discarded plastics serve as a substitute for coke and coal. Now she and her lab team are looking into more alternatives, such as macadamia nut shells and other agricultural waste products, as well as used electrical equipment. If she had more time, she would be looking into more. “I’ve got so many things on my list of waste,” she says. Sahajwalla grew up in Mumbai, India, the daughter of a civil engineer and a doctor. Her parents wanted her to study medicine, but she had her own ideas. “In my eyes, engineering was always the obvious career,” she says. “That’s how I see myself, very much as the engineer. I can’t imagine life being anything else.” At the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, Sahajwalla was the sole woman studying metallurgy, and she graduated at the top of her class. She moved to Canada to complete a master’s degree and then did her PhD at the University of Michigan in the United States.

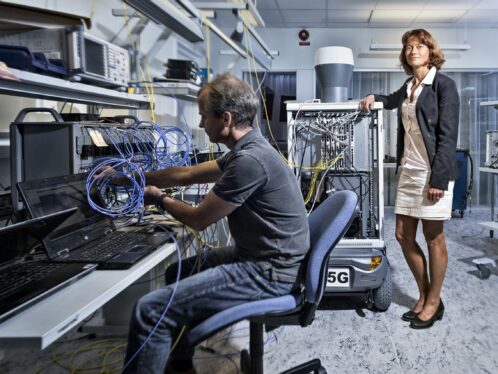

As she was delivering a paper at an international conference in the US, some Australian delegates approached Sahajwalla with the possibility of a job “Down Under”. She finished her PhD on a Friday in 1992 and on the following Monday was at her desk in Melbourne, working for Australia’s leading scientific body, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). She stayed at CSIRO until 1994, when she took an academic post at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. Much later, during a sabbatical in the US, she spent some time in steelmaking plants, and it was there that she started to consider how the manufacturing process might be modified. Looking at how furnaces operate, she began experimenting with other input materials, such as polythene in the form of old shampoo and detergent bottles. She moved on to car tyres (“Well, why not?” she asks), and she discovered that they were an excellent – and environmentally friendly – substitute for coke. After three years of lab work, she teamed up with Australia’s largest steel manufacturer, OneSteel, to put into practice her theory of using shredded tyres as a partial replacement for coal and coke. It worked to such a degree that by mid-2013 OneSteel (now Arrium) had prevented 1.6 million tyres from going into landfill sites and brought significant energy savings to the company. Sahajwalla’s breakthrough has earned her several awards, but it also inspired her to look further at waste, a subject about which she speaks passionately. Mid-conversation, she suddenly drops behind her desk and pulls a well-worn pillow out of a recyclable bag. “What do we do with this once we are done with it?” she asks. “It’s horrible, and it’s useless.” Sahajwalla wants to identify the materials inside the greying old cotton cover and find other uses for them. A quick peek behind the desk reveals at least a dozen other bags containing all manner of waste. If Sahajwalla had her way, the environmental mantra of “reduce, reuse, recycle” would be appended with a fourth term: “re-form”. This would encourage us to look at the many ways our waste could be transformed into other products, she says. “The reason why we think, ‘OK, that’s done, it goes into landfill’ is because we are just thinking of a glass as glass or plastic as plastic,” Sahajwalla says. “If we do all the three Rs and we still put stuff into landfill, that means we’ve got to make quite a radical shift in the way we actually use recycling. Where scientists and engineers need to come in is contributing to that fourth ‘R’.” Sahajwalla believes that a holistic approach to waste is the way of the future. She says it’s too expensive and impractical to separate materials in, for example, a junked car or a busted mobile phone. It’s far better, she says, to investigate how the materials within these products might react with each other more effectively in high temperatures than to separate them into single streams. In traditional electric arc furnace steelmaking, coal and coke are injected into the furnaces to help produce the chemical reactions needed to make the steel. In the polymer-injection technology developed by materials engineer Veena Sahajwalla, old rubber tyres and plastics replace some of the coke. The carbon and hydrogen in the tyres does the same work as the carbon in coal and coke – acting as a reducing agent to convert iron oxide into iron. The process has been used by the University of New South Wales’ industry partner Arrium (formerly OneSteel) in its Australian operations since 2008 and has saved an estimated 1.6 million tyres from landfill. Moreover, the tyres have proved more efficient than coke in the process, so their use has reduced the company’s power consumption. The patented technology has been sublicensed to a plant in Thailand, and Arrium is also in talks with other international steelmakers.

In May 2013, Sahajwalla was invited to give the Howe Memorial Lecture, the global iron and steel industry’s most prestigious lecture. She used the opportunity to emphasize the potential of waste, telling her audience: “This could well be the future, that we could be seen as the industry that helps everybody else clean up their act.”Greener steel