Winds of the past

A replica of a historical Swedish trading vessel will add a new chapter to history books when it retraces the route the original vessel took to the Orient during the 18th century.

Summary

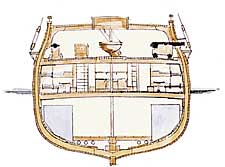

The replica trading vessel, the East Indiaman Götheborg III, which is currently under construction in Gothenburg, Sweden, will have the same hull lines as the original 18th-century ship, which had ample cargo room to maximise profits. The content, however, will be different, including, for example, modern navigation and security equipment, a freshwater system with showers and toilets and a modern kitchen and ventilation system. The original vessel had no propellers or motors, while the replica will have two Volvo Penta engines with a combined output of about 1,000 horsepower. To fulfil security requirements, it will be equipped with emergency generators, watertight bulkheads, life rafts and emergency exits. A bilge pump, a fire extinguisher and an automatic sprinkler system will be installed for fire emergency. The rigging will be based on the type of rigging used during the 18th century, although it will comply with modern safety precautions and requirements. The actual rigging work and the production will be carried out by hand, using traditional methods and tools. In the old days, trading vessels usually had about 30 cannons on board as a safeguard against pirates and enemies. The replica will carry 14 six-pound cast-iron cannons for saluting upon arrival at various seaports. The ship is equipped to carry 80 people, compared with the 120 to 140 people typically on board during an 18th-century voyage. Back then, poor hygiene, illness, malnutrition and challenging weather conditions caused many deaths among the crew, so extra manpower was necessary. This ship will have on-board medical staff.

A replica of a historical Swedish trading vessel will add a new chapter to history books when it retraces the route the original vessel took to the Orient during the 18th century.

At the Terra Nova dock in Gothenburg, Sweden, a replica of an 18th-century trading vessel is gradually taking shape, gaining greater magnificence as each day passes. When it is completed, the ship will become the first replica of its kind to actually make an ocean voyage. And the voyage will be nothing short of half way around the world – to China, which the original ship visited on several occasions on trading missions during the heyday of Svenska Ostindiska Companiet, the Swedish East India Company. (See For all the tea in China.)

“What we’re doing in this project is not only writing Swedish history but also writing Chinese history, and strengthening relationships between the different countries,” says Jörgen Gabrielson, CEO of the modern-day Svenska Ostindiska Companiet, founded in 1993.

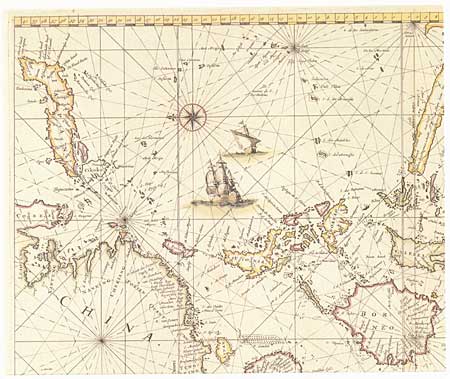

The itinerary for the ship, scheduled to start its journey in the autumn of 2004, includes stops in Spain, Brazil, South Africa, Australia and Indonesia before the final destination – Guangzhou, China. At each port, exhibitions and activities to promote Swedish culture and business will take place.

“What we have done in the past is something that connects us with the future,” says Gabrielson, who believes the project will have a positive effect on Swedish-Chinese trading relations. “It’s important to have a relationship with [China] and with other countries,” he says.

Identical twins

Physically, the replica, named the East Indiaman Götheborg III, will look almost identical to the original East Indiaman Götheborg I, which was built in 1738 and sank right outside the harbour of Gothenburg in 1745, on returning from its third voyage to China. There was also an East Indiaman Götheborg II, the second largest ship owned by Svenska Ostindiska Companiet. It sank in 1796, 10 years after it was launched, in Table Bay in what is now South Africa.

Inspiration for the modern-day Götheborg project came from the excavation of the original ship. Salvage work began immediately after the wreck occurred and continued during the centuries that followed. From 1986 to 1994, marine archaeologists excavated the wreckage and recovered tonnes of porcelain, tea, ginger, silk, spices and more from the cargo, as well as personal belongings of the crew.

Joakim Severinson, master shipbuilder of the replica, was one of more than 100 divers who participated in the excavation work. Severinson, a long-time sports diver, had also worked with large wooden ships as a shipwright prior to joining the excavation project in 1986.

Severinson recalls first discussing the idea of building a copy of the Swedish East Indiaman in 1992, with others involved in recovering the wreckage. At that time, the Dutch had already built replicas of two of the country’s old trading ships, the Amsterdam and the Batavia, for museum display. “We talked about what it must have been like to sail such a ship in the 18th century,” he recalls.

When the idea came up to actually sail a replica, Severinson says, “I think many people thought we were a little bit crazy. And maybe we were.” The current ship-construction project, which started in 1996, differs from the Dutch projects in that the East Indiaman Götheborg III is built in full compliance with international regulations for sea traffic so that it can sail the seas.

Myriad challenges

There are many challenges facing Severinson and his team of 137 shipbuilders. First of all, very little of the original ship was preserved, and neither drawings nor models of the ship were available to serve as blueprints. In fact, shipbuilders of the past often didn’t use drawings or rules – they carried the blueprints inside their heads. To come up with a drawing of the hull, Severinson relied on the details found during the excavations, as well as documents from historical archives. Ship models, drawings of other trading vessels from the same time period, shipbuilding rules and a book about rigging also proved to be very useful.

It took Severinson about two years, from 1993 to 1995, to complete drawings of the hull. “Most of the ships at that time looked almost the same. There could be small differences in length and ornaments. But as for the hulls, they were built almost the same way,” the shipbuilder points out. “We can’t say we’re building an exact copy of the original ship, but we are building a typical mid-18th century Swedish East Indiaman with all that we know about the original ship. So it’s as close as we can get.”

Another challenge during the course of construction is the search for materials. Building an 18th-century ship requires many raw materials that are not as easily found today, such as pine and oak wood with specific measurements and age, tar, iron and sail fabrics. All materials have to be custom-made, which, says Severinson, takes a lot of searching. Often only one company in Europe, or in the world, can deliver a particular material.

But the biggest challenge, he says, is to hide the modern equipment on board, so that the ship looks as authentic as possible. This means the modern equipment has to be placed as far below deck as possible, which takes a lot of patience and compromise. But the use of modern technology is critical to the success of the enterprise because the ship must fulfil the requirements of international authorities. “We can’t make any exceptions,” says Severinson.

Financing

The last big challenge is financing. The construction of the East Indiaman Götheborg has taken longer than expected, due to difficulties in raising funds. The budget set for the project is 300 million Swedish kronor (about 30 million euros). So far, about 95 percent has been raised. For the remaining part, CEO Gabrielson is working with several sponsors to raise the funds. Some 130 Swedish companies have contributed to the construction of the ship. Svenska Ostindiska Companiet is looking for five to 10 large international companies to participate in funding the China voyage itself.

Gabrielson’s vision is for the East Indiaman Götheborg to make other journeys in the future, if the first one turns out to be successful. In 2006, after its return to Sweden from China, the ship is scheduled for a new promotional voyage, via Norway and through the Panama Canal to the United States. It will then continue to Tokyo, Japan, and finally dock in Shanghai, China, to participate in the 2010 World Expo. “We are going to build business relationships with Japan, the Philippines and Singapore, to promote Swedish companies in that area,” says Gabrielson. “If we’re going to fulfil [the vision], it depends on the right timing and luck.”

Joining the party

For several years now, SKF has been one of the sponsors of the East Indiaman Götheborg project. Danerik Hägglund, director of internal communications at SKF, says that although the company rarely sponsors individual projects, it is supporting the Götheborg project because the endeavour parallels the scale of the global expansion undertaken by SKF’s founder, Sven Wingquist, in the 1910s and 1920s, and because of its commercial potential.

A connection with the Götheborg project may well benefit SKF in the future – in particular, in light of SKF’s emphasis on its business development in China, Hägglund says. He also says SKF can benefit from China’s tradition of building long-lasting business and diplomatic relationships.

The company plans to participate in various commercial activities during the ship’s stopovers in each harbour, says Hägglund, noting that SKF would benefit a great deal provided that other strong global brands are present during the voyage.