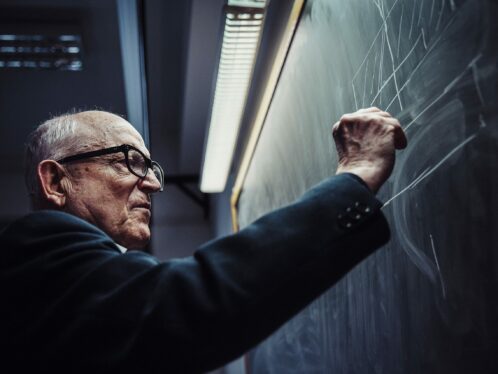

A dream come true

Archaeologist Marc Waelkens turned a childhood fascination with Turkish antiquity into an illustrious career. In the process, he profoundly changed the way archaeology fieldwork is approached.

Small children often have big dreams about the kinds of jobs they’ll do when they grow up. The reality is, though, that very few go on to become the astronauts, pilots or firefighters they wanted to be at age 5 or 6. Archaeologist Marc Waelkens, an emeritus professor at the University of Leuven in Belgium, is one of the rare exceptions. In the summer of 2013 he concluded a long and illustrious academic career that had its origins nearly 60 years earlier, in his boyhood. “I can tell you precisely what sparked my dream, and when it happened,” Waelkens, 65, says from his home in Leuven, about 25 kilometres east of Brussels. “I was 6 years old when I read a story in a comic book about the exploits of Heinrich Schliemann. He’s the man who discovered Troy and proved, against all odds, that the legendary city actually existed. I knew in that instant that I wanted to be an archaeologist in Turkey and nothing else.” Waelkens’ academic career started in Ghent in Belgium’s Flemish region. During the second year of his ancient history degree he paid his first visit to Turkey and the site of Pessinus, a ruined city in Asia Minor. The experience proved to be the beginning of a long relationship with the country. “That was 1969, and I have been back to Turkey every year since,” he says. After completing his PhD in 1976, Waelkens took a post as a researcher with NFWO, the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research. There he made a name for himself by participating in excavation projects in Turkey, Greece, Syria and Italy. In 1983, Waelkens was part of a British archaeological team that visited Anatolia, Turkey, to conduct a survey of the site of the ancient city of Sagalassos. While the city’s theatre was exposed at the time, the majority of its remains were largely untouched, protected from exploitation by the remoteness of the site and a lack of access roads. But the site promised to yield interesting finds. Sagalassos had enjoyed a rich and varied history and had once been home to a forward-thinking citizenry who emulated the Roman way of life, before earthquakes and other challenges led to the city being largely abandoned in the 7th century. At the time of Waelkens’ visit, archaeologists were undertaking survey work on unspoiled sites in the Western Taurus Mountains as a matter of urgency to help preserve them, and he happily pitched in. “That first visit changed my life,” he says. “It was love at first sight, and I knew I had found my destination. I remember how one day an eagle accompanied our minibus all the way from the site to the house where the team was staying. It was as if we drove under the protection of Zeus himself.”

While the British team soon moved on to other sites, Waelkens decided to stay at Sagalassos. In 1989 he began small-scale excavations on the site under the auspices of the Turkish Archaeological Museum of Burdur, with five workers and five archaeologists. Then, in 1990, he was granted exclusive excavation rights to the site by the Turkish government. By then he had left Belgium’s University of Ghent and found a new “home” at the University of Leuven. From then on, everything that Waelkens did would somehow be connected to the city that with hardly a trace of irony he calls his “bride”. Each year he would spend a few months on the site, walking at least 20 kilometres a day with heavy gear and cameras. He wrote many books and hundreds of papers about Sagalassos and became a tireless fundraiser for the excavation and preservation work. Meanwhile, he founded the Leuven Centre for Archaeological Sciences and several international scientific networks, received many awards from all around the world, and in 2009 he was knighted by King Albert II of Belgium. “I hardly ever sleep more than three hours a night, and that pace hasn’t abated even a bit since my retirement,” Waelkens says. “It seems I just can’t stop.” Apart from the numerous priceless artefacts and ruins Waelkens has unearthed at Sagalassos, his greatest achievement, according to many in his field, is that he has changed the way researchers approach classical archaeology. He introduced a comprehensive methodology to the field that combines disciplines as varied as archaeobotany, palynology, archaeozoology, anthropology, geomorphology and geology. This innovative approach has yielded an unprecedented insight into Sagalassos and many other sites. “We have analyzed close to 2 million fish bones and artefacts made of bone,” Waelkens says. “Thus we know that fish from the Nile were on the menu for many centuries. And we dated the earthquake destroying the city in the early 7th century by studying pellets from owls that once nested in the ruins of the bath complex.” The comic book that started Waelkens’ journey now hangs framed on the wall in his study. Has the dream he had as a 6-year-old been realized? He pauses briefly to reflect. “Better than that,” he says softly.