Summary

Bearings in Grand Prix cars

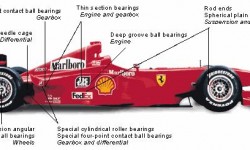

Today’s Formula One cars are highly sophisticated pieces of machinery, boasting electronic sensors and complex on-board computer systems. Yet at the heart of every wheel, every change-by-wire sequential gearbox, every scavenge pump on the engine, and at the end of each suspension wishbone or push rod is a bearing.

SKF has a long relationship with the racing industry. The most obvious example is the company’s relationship with Ferrari, a relationship with a history that is longer than that of the modern Grand Prix era. Somewhere in a modern Grand Prix car you will find an example of almost every type of bearing SKF manufactures. Some are standard pieces, straight from the catalogue; others are custom designed and manufactured to match the peculiar requirements of this most demanding of industries.

The dedicated SKF race engineering team provides design, calculation and analytical support to race teams competing in the world’s major championships.

Drivers of Formula One racing cars get all the glamour. But the plot that keeps everyone coming back to the track is written by the engineers behind these powerful machines.Monza, Italian Grand Prix, 1996. Chief race engineer Giorgio Ascanelli has a dilemma.

With a few laps to go Michael Schumacher is leading, but his Ferrari is getting dangerously low on fuel. Ascanelli knows it’s time to call Schumacher into the pits. But the German’s lead over second-placed Jean Alesi is not enough to get him in and out before the Frenchman overtakes. In split seconds, the engineer analyses the row of computers in front of him. He takes a deep breath and decides.

“I left him out an extra lap to gain more time on Alesi,” he recalls, eyes blinking nervously with the memory. “When he came in, his car had zero fuel pressure. That’s about 300 grams in the tank.” Schumacher went on to win the race. Or so 100,000 ecstatic Italians thought.

“Giorgio won the day,” says Gustav Brunner, technical director with Minardi Formula One racing team. “If the Ferrari had run out of fuel, then Giorgio would not have left Monza alive; 100,000 Italians would have lynched him.”

The hidden world of the engineer may lack the beautiful women and the obsessive characters that have turned Formula One into sport’s best soap opera. But the plot that keeps everyone coming back is written in the pit lane.

Brunner, a former designer with Ferrari who has spent 30 years designing Formula One cars, says: “If you took $100 million and played on Wall Street, it would be nothing compared to the life we lead.” Decisions are made in split seconds – not by the driver, but by the man on the pit wall.

“In 10 seconds you must decide to bring a driver in or keep him out, fuel in or fuel out, wet tyres or intermediates, which driver is on a one-stop strategy, who is on two – and all the time you watch the screens, the times, the lap. It’s hell, believe me, it’s hell.”

Army of engineers

The sheer number of personnel used in the Ferrari pit lane – 50 to 55 – is eye-opening. Each car, including the spare, has a chief mechanic plus a couple of wheel men (Formula One teams take more than 150 tyres – 13 sets of four per car – to Grand Prix events). Then, there is a gearbox mechanic, an engine mechanic and a race engineer and his support. With barely a second separating winner and runner-up, races are won and lost here – not just in the 90 minutes of the Grand Prix but in the three days that separate the first practice lap from the chequered flag.

Engineers have 120 minutes on Friday and 90 on Saturday morning, followed by an hour of qualifying, to coax the best out of what ex-world champion Jackie Stewart once called “a thoroughbred race horse.”

“The race engineer’s job is a strange activity,” says Ascanelli. “One has to collect all the technical parameters that affect the car’s behaviour: aerodynamics, engine mapping, gear ratios, brakes, tyres and so on. I would say an error margin of 1 percent is satisfactory.”

It is the engineer’s job to help build “the special relationship” between driver and car. “Whatever you do, the driver needs to have confidence in his machine,” says Brunner.

In modern-day Formula One, there are few technological revolutions but much day-to-day evolution. The car starts life as a computerised model with teams striving throughout the season to make it fit reality. Every year Ferrari conducts an estimated 50,000 kilometres of tests and assembles 800 engines in the painstaking search for perfection. In 15 years, Ascanelli has witnessed the development of 21 engine designs.

“There are thousands of little steps, but there is no revolution,” says Brunner.

Rulebook changes

In the 1970s, the first winged cars left other teams trailing in their slipstream. Now the rulebook leaves little room for great technological leaps. Instead engineers edge back the technological envelope with minor adjustments. Last year the McLaren MP4/13 dominated the opening Grand Prix events because it used wider front tyres. The current Ferrari F399 looks like last year’s car, but it weighs 40 kilograms less.

Even if there are breakthroughs, they are invisible. There are 15 metres of electronic cable beneath the bonnet of a Formula One car, integrating sensors that flash information to the pits, the “drive by wire” throttle and other electronically controlled systems. The traditional nuts-and-bolts mechanic is a dying species in this world. “Formula One has become more specialised. `A jack of all trades but a master of none’ is less valuable than it used to be,” says Ascanelli. “From an artisan trade, it has become an industry.”

Ferrari’s factory at Maranello, which employs 400 staff, has an entire floor dedicated to research and development with structural engineers, carbon fibre engineers and experts in electronics, suspension and software. Even the driver’s seat has its designer.

“The man who designs the front of the car does not know what is going on at the rear and vice versa,” says Brunner.

Two decades ago, when teams were still family-sized, Brunner’s title of technical director did not exist. Now he is one of the few persons with an overall view of the car. It is a powerful position. Brunner still recalls when Enzo Ferrari, the late founder of Ferrari, looked at him and said: “Here’s the factory. I want three red cars here in four months.”

The days when the Wolf team cut metal out of a crash barrier at the 1979 Argentine Grand Prix to repair the bodywork of a car have long gone. But it is still possible to get a taste of the pioneering days at Minardi, perennial back-of-the-grid starters.

Art as well as science

Whereas Ferrari’s reception area is emblazoned with black-and-white photos of previous world champions, the only trophies on display at Minardi’s headquarters in Faenza are plaques commemorating participation in 15 world championships. A lone fourth-place in 1995 remains the best finish. Yet Brunner says he left Ferrari to taste the grass roots of the sport. The designer, who still insists on pen and paper for his inventions, believes Formula One minnows such as Minardi can still match high-tech giants on the drawing board.

“If it were only science, McLaren would have won the last seven championships because they had a thousand engineers and hundreds of millions of dollars,” he says. “But it is still 50 percent art. There are specialists, but only if you have a good overall concept will it give a good thing.”

In 1998 Ferrari spent some 500 million lire (US$280,000) per day, with the car itself costing US$1 million. Minardi will spend an estimated 70 billion lire (US$39 million) this season. Hardly surprising, when you consider a Formula One car’s rear-view mirror costs 875,000 lire (US$480). Ultimately, however, the designer is not just playing with the owner’s bank balance but with the driver’s life.

“We have very valuable people sitting in those cars, and you have to give them the chance to make mistakes and not get hurt,” says Brunner.

Perhaps it is this knowledge that makes the engineer willing to take a back seat to the driver on race days. “A hundred million people watch a Grand Prix on Sundays because of the driver. I think they want to know about the power and passion, not how big a bearing is,” says Ascanelli modestly.

But, despite its own image of scientific efficiency, the power and passion of Formula One does touch the hidden world of engineering. “When you clean the visor of your driver and send him out for the final laps, your eyes are streaming,” says Ascanelli. “And when you know he’s going to do it and he does, well, that’s nice.”

Chris Endean

a journalist based in Rome

photos Antonello Nusca