Underground challenges

Tackling the biggest, the toughest, and the longest tunnels in the world – Herrenknecht AG constantly masters new challenges underground.

Tackling the biggest, the toughest, and the longest tunnels in the world – Herrenknecht AG constantly masters new challenges underground.

The casual visitor to the cityof Schwanau, in Germany, wouldn’t suspect that this town of half-timbered houses is home to a world-leading producer of the full range of mechanical tunnelling machines. But those who get off the nearby Autobahn to stay at the Schwanau Hotel can’t miss the hulking pair of white-painted portal cranes looming over the adjacent

industrial complex. And if they take a closer look at the complex that makes up the headquarters and manufacturing plant at Herrenknecht AG, they’ll also see a huge concrete ring outlining a four-storey glass wall on the administration building – a ring whose 14.2-metre diameter matches that of the fourth tunnel under the river Elbe in Hamburg, one of Herrenknecht’s many record-breaking projects.

It is less than 30 years since founder Martin Herrenknecht opened an engineering office in a one-bedroom apartment in Schwanau, a city situated a few kilometres from the French border, between Germany’s Black Forest and the Rhine river. Since then, Herrenknecht has constantly increased its store of expertise, allowing it to build high-technology tunnelling equipment and systems to meet the needs of builders in the widest range of geological conditions on all continents. Right now, Herrenknecht equipment is at work on the world’s longest train tunnel, grinding away 75 kilometers of hard rock under the St Gotthard mountains, with a completion date of 2015. For the Elbe river roadway tunnel project, completed in March 2000, Herrenknecht developed new sensors to detect boulders and other irregularities in the seven types of soil that the machines would pass through. It also pioneered, together with the customer, a new cutting wheel that made maintenance easier and safer. And in Cairo, Herrenknecht supplied equipment for tunnels to drain groundwater from under houses of worship in the city’s old town, leaving the foundations intact and basement vaults accessible to future generations.

“We always take on the most difficult, the biggest and the longest projects,” says Achim Kühn, manager of public relations and investor relations at Herrenknecht AG. “And if the competition snatches one from us, we get back with the next one.”

Aside from a can-do attitudeand a hunger for new challenges, an important factor in Herrenknecht’s success has been its open, direct and cooperative relationships with customers. Whether for subway tunnels in Guangzhou, China, sewage pipes under a major highway in Rio de Janeiro or water-supply pipes for irrigation on the Indian Ocean island of La Reunion, Herrenknecht must forge relationships of trust with authorities and investors who commission the projects and the companies responsible for carrying out the work.

“We’re at the end of the supply chain, and we have to guarantee maximum dependability,” says Kühn. “We can’t hide problems. In any case, customers can always give Mr. Herrenknecht a call.” Josef Gruseck, the company’s authorized signatory, says Herrenknecht’s efforts to build relationships with customers have paid off, particularly in Switzerland, where the company has supplied equipment for 28 tunnel projects. “We have a very high degree of loyalty there,” says Gruseck. “We have to be able to look our customers in the eye 20 years down the line.”

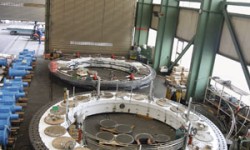

Few of the millions of peoplewho ride through tunnels built by Herrenknecht machines will ever see the likes of tunnel boring machines such as the record-breaking 15.2-metre-diameter “earth pressure balance shield” delivered to a highway site in Madrid in the summer of 2005. It is so large it could not be put together inside one of the six hangar-like construction buildings on Herrenknecht’s 43,000-square-metre site. Instead, it had to be assembled under the white portal cranes outside. And few probably guess at the complexity of these gigantic machines – the biggest of which can reach 440 metres in length and more closely resembles a factory than a simple drill. Under the right geological conditions, tunnel boring machines can simultaneously chip away at hard rock, carry away the broken rock pieces on conveyor belts, transport and install the concrete slabs that form the new tunnel, and feed a constant supply of data on positioning of the machine and conditions ahead – all while supplying workers with fresh, cooled air and keeping them safe well behind the machine’s cutting surface. In softer earth, as in the Madrid project, the machines can inject foam or a viscous solution into the soil ahead of the machine to help stabilize the fresh opening and make removal of soil easier. And in all cases, Herrenknecht engineers must plan for the need to safely and easily change cutter disks on the cutterhead, minimizing the possibility of the shield getting stuck in the tunnel and avoiding disturbance of the surface above the drilling site, particularly in big cities. “The average person doesn’t think much about everything that could go wrong with a tunnel project,” says Kühn.

Above ground, Herrenknecht hasother stresses to deal with, particularly ever-tightening deadlines. Customers demand just-in-time completion to avoid traffic bottlenecks and extra workdays. At the same time, more and more tunnels are being commissioned by private investors, who pay ever-closer attention to the return on their investment, Gruseck says. Herren-knecht’s solution to the increasing deadline pressures has been to develop even better relationships with customers and suppliers in an approach the company calls “teamwork tunnelling” or “full-service tunnelling.” This means tailoring project-specific services to customers’ needs. These include global spare parts management, around-the-clock maintenance and repair services, and, in the case of developing markets, even complete systems encompassing concrete supply, logistics and climate control. For this approach to be successful, of course, Herrenknecht must be able to count on the utmost reliability of suppliers, such as SKF.

As Herrenknecht nears its 30th birthday, the company is showing no signs of slowing down. Instead it is continuing to set a fast pace. Total sales of Herrenknecht group reached 433 million euros in 2004. Herrenknecht’s sixth assembly hall in Schwanau was opened that year, and less than a year later a seventh was in planning stages. Asked by a visitor about the need to buy up more of the adjacent farmland, Kühn smiles and says, “It’s already been purchased.” Looking far beyond its home base in Europe, Herrenknecht has built up a presence in China, which is now, besides Europe, the company’s largest market, a fact underlined by the visit to the company headquarters by the Chinese vice minister of water resources in late 2004. In the autumn of 2006, Herrenknecht is poised to set a new size record, for the delivery of a tunnel boring machine that is 15.43 metres in diameter. The machine is needed for a road tunnel in Shanghai. And having expanded the range of tunnelling diameters for which Herrenknecht can supply equipment from 100 millimetres to nearly 16 metres, the company is now exploring new territory underground: Starting in Germany, Herrenknecht is planning to supply equipment to bore 5,000 metres below the surface, to transport geothermal energy to the surface.

When Herrenknecht’s engineersmeet in a conference room next to Gruseck’s office to tackle such challenges, they may well be inspired by a breathtaking poster on the wall. It’s the image of two people using ropes to climb to the craggy summit of a peak in the Dolomite Alps in Italy. And the caption under the picture reads: “By striving for the unreachable, we produce the best possible results.”

Systems that cut the world’s hardest rock

SKF has been supplying slewing bearings to Herrenknecht since 1987. These bearings, which include gear and bolting, constitute the “heart of the machine,” according to SKF engineer Reinhard Kirsch. They must transfer all loads between the rotating cutterhead wheel and the rear of the tunnel boring machine. In working almost 20 years with Herrenknecht, SKF has built a solid relationship with the company’s engineers and its authorized signatory, Josef Gruseck. “SKF is very committed to developing new products with us,” says Gruseck, noting that most of Herrenknecht’s projects have the character of a prototype. “There’s a very high level of communication, both on the technical level and when it comes to commercial considerations.”

In 2005, that relationship paid off particularly well for SKF. In February, SKF supplied five taper roller bearing test samples for the giant cutterhead wheels that do the heavy work of carving away hard rock or mixed rock and soil deep under the earth. By September, Herrenknecht had put in an order for 1,000 cutter bearings.

Kirsch is very conscious of the responsibility that comes with supplying bearings that must withstand pressures of up to 27 tonnes when boring into solid rock – for example, the main bearing for a blue-and-yellow-faced cutterhead on a tunnel boring machine that was being assembled in the fall of 2005, to be sent to the city of Almaty, Kazakhstan, to construct a subway tunnel. “You can change cutting wheels on the job, but you can’t replace the main slewing bearing,” says Kirsch.

SKF also supplies complete lubrication solutions from Willy Vogel, including grease lubrication for shields, joint bearings and grippers and oil circulating lubrication for main bearings and drives.